It’s been a little over three weeks since my last update, which is because I have been largely focused on reading and writing about larps and nanolarp design from a critical, reflective point of view. I finished a solid first draft of this paper last Thursday, and am letting it sit a bit before I write a talk and make slides based on it for this year’s CGSA conference in Regina. The paper is sitting at around 9500 words…which is a lot more than I intend to keep, so rewriting and editing is a future challenge on the docket.

I’ve been making some progress on my dissertation work since my last post. I have done some experimentation with the micro:bits that I ordered, and found that they do communicate in an easy, friendly way, as advertised.

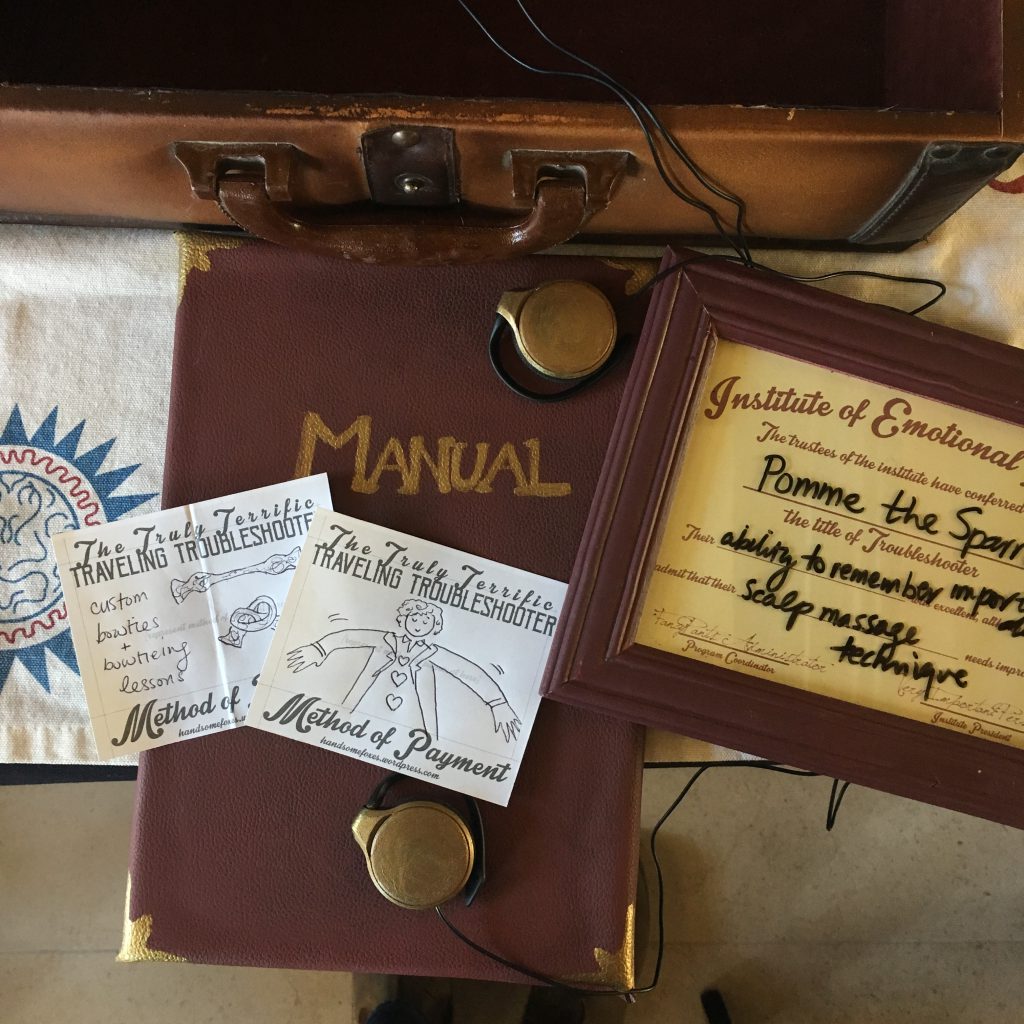

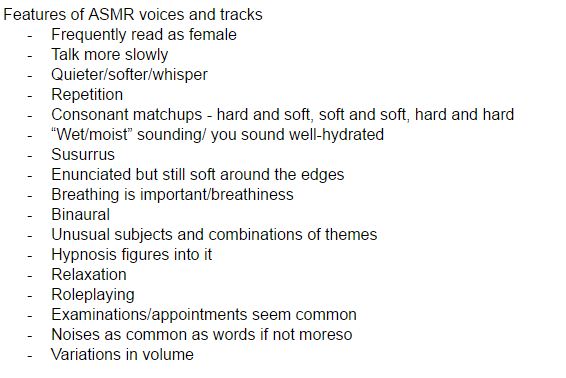

I built code that displays a simple graphical pattern in LEDs when they receive a transmission from each other. This could be the signal for the “shoulda said” aspect of my first dissertation game. I also ordered a number of new electronic components: three Floras and a number of Neopixel rings that can easily be sewn onto textiles. I also made a sizable Fabricville order of different fleece materials for making puppets. This is reflected in the ads I am being shown on the internet, which have been asking me whether I would like to meet other single seniors in my area.

I have also bought a simple puppet pattern to give me an idea of what will be involved in making a traditional hand puppet. I feel confident in my ability to wing it, but that doesn’t mean that one of these patterns won’t turn out nicely, with a lot less effort on my part.

I’ve received updated ethics approval after submitting amendments regarding group playtesting!

I have also started to think about and draft the Background chapter of my dissertation. Though I’ll no doubt have to add to it before my final dissertation, having a version of the background chapter seems like a good goal, especially since the other activity that I have been engaged in is a great deal of reading. In the past few weeks, that has taken the form of the larp research that I have been doing, but I am now reading Adrienne Shaw’s Gaming at the Edge. A friend of mine has also recommended, based on a brief description of my planned dissertation game, that I read about Psychodrama, and loaned me a book with a chapter on it. Also, a project report about the followup to “Hybridex” has just been published about Hybrid games, and is just perfect for my background chapter.

The reason that one of the words in this blog title is “anxiety” is because I am feeling anxious about my dissertation. I understand that this is probably normal, but, I want to faithfully document these thoughts and feelings as well as I can for the autoethnographic process.

The first feeling, common to grad students and probably faculty members in academia everywhere, is that I am not getting enough done everyday. But, I know that I have been doing well, and doing a lot, on the whole, and making sure to take care of myself and others. I’ve done grocery shopping, gone to the gym, taken my cat for walks, cooked many sumptuous and delicious meals, and generally done a good job at those parts of being an adult human. I took care of my family and friends as well, being there for them emotionally, and finishing a first draft of two separate projects that I have been working on for about two years, with my father and my brother. I also wrote 9500 words in about two weeks. 9500 academic words! That’s a lot — so it shouldn’t surprise me that I’m feeling a bit tired, and haven’t done as much writing on the Background chapter. The reading is going well, and it takes time to read — I have to remind myself of that as well.

The next source of anxiety is related to Tom’s job, and unfortunately, there’s not much I can say about that, except to say that some of my days have been spent helping him, and I have no regrets there.

The next feeling is the feeling of time pressure: if you know me, you may know that I occasionally call myself a reverse procrastinator — that I like to get things done long before they are due so that I don’t have to worry about them. In planning my dissertation timeline, I wrote off January entirely and gave myself an additional two months for my first dissertation game project because I had a feeling that, with everything going on in my personal life, and with this being the first OFFICIAL PROJECT of my dissertation, that there might be some fumbling and stumbling blocks.

This brings us to what seems like a very important source of anxiety: designing the game itself. Generally speaking, when I make a project, I have the freedom to let the project be what it will be, take the time that it will take, and I don’t have to worry that much about making an “amazing” game. I am feeling a lot of pressure, somehow, to make this first dissertation project the best game ever, and feel like somehow the scope has to be bigger than my usual work. But that’s entirely not the point of these projects: I’m not studying whether the game that I make is any good, I am studying the process of making it and archiving it. I’m collecting data about the project and what people think about it. I’m studying my own game-making practice. I know that I will likely make better games, and I will likely make worse ones. I know that I also generally do my best work in small teams with other folks, and that for the most part, I intend these games to be solo. I know that I will be pushing against the limits of my skills, bettering myself, and learning entirely new skills.

Honestly, that’s a lot of pressure to put on six months of work that will include so much of the other necessary parts of grad school, even if they aren’t officially mandated: the reading, the writing, the preparing for conferences, the meetings, the interacting with the rest of my community. And yes, this all feeds into making this game, but at some point, I have to start making it.

Another problem with designing this game that I am having is that because I am putting heavy emphasis on the design of the physical objects involved, part of my brain is wary about working “for nothing”: I don’t want to start working on the physical crafting components, and have to scrap/restart them because the game has totally changed. Usually, that means I would just rapidly prototype with the cheapest available materials and be done with it. But that presents two problems at the moment:

— Fort McMurray is remote. I can’t just pop by the electronics store, the fabric store, or whatever other store to get more materials. There’s also no one or two-day shipping to Fort McMurray. If I need an object, I have to plan for it ahead of time.

— In this game, it feels like the interaction will only “feel” right and complete with the final objects because of their materiality. So, prototyping without a finished object is possible but presents some challenges for the imagination.

Another source of anxiety is working remotely in Fort McMurray: in addition to the difficulties sourcing materials, I am struggling with the fact that I am not in my usual creative environment. I have grown used to making things at the TAG lab, surrounded by other researchers, creators, and friends, and being able to casually discuss my project. I would much rather be working on these projects in Montreal.

…However, all of my crafting materials (and there is a lot of it) are up here in Fort McMurray, so popping back and forth to Montreal as I have been doing since the beginning of last year simply isn’t possible in this context. Or at least, it doesn’t feel very possible without a heck of a lot of money spent on checked baggage or shipping.

Thankfully, I should be moving back to Montreal soon. At the very latest, I am teaching a course in Winter 2019, and so I should be back in the city for my third dissertation project, at least.

This brings me to another very present source of anxiety or trepidation: Will this game be any good? Is “Flip the Script” a good idea? Won’t there be issues with constantly interrupting the play? How should I handle those issues? Should I make something a little less open with a little more story to it? Will this game be meaningful? Will it be reflective and critical? Am I taking advantage of the digital components enough? And, related to that: Am I running out of time?

Well…these are the things that are on my mind, and even just writing about them as been helpful. I hope this documentation will be helpful to future Jess as they write their dissertation. Certainly, the discussion about time limits, and the uncertainty about designing to spec and within certain limitations (that it has to be a game that explores physical-digital hybrid design, that it has to be made in roughly six months, that it should be about critical, reflective subjects) reminds me of my work with Rilla about critical game design, where a number of designers designed according to a prompt that we provided (you can read our chapter in Game Design Research)

Your faithful autoethnographer,

Jess