You already know how amazing this year’s Critical Hit participants are. But did you know that in one form or another TAG’s game incubator program has been around for a while and helped to produced some fantastic games. Critical Hit co-director Charlotte Fisher conducted an interview with Richard E Flanagan, one of the creators of FRACT to give us a chance to check in with past participants, see what they’re up to and how their teams and games are doing today.

Meet our Alumni: Phosfiend Systems

by Charlotte Fisher

A little while ago, I had the pleasure of interviewing Richard E Flanagan of Phosfiend Systems, the creators of FRACT. Many of you may not be aware that they got a boost during Critical Hit’s pilot incubator (which at the time was called the Montreal Games Incubator).

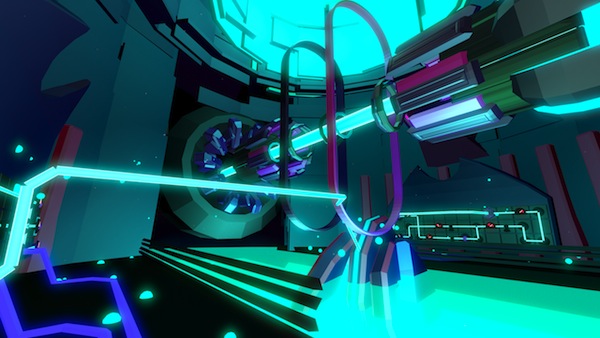

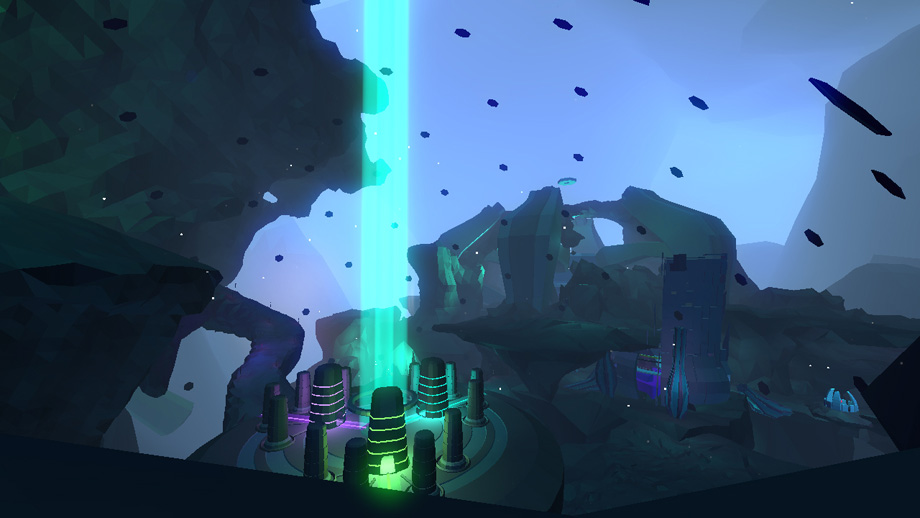

As written on their website: FRACT is a musical exploration game. You arrive in a forgotten place and explore the vast and unfamiliar landscape to discover the secrets of an abandoned world that was once built on sound. As you start to make sense of this strange new environment, you work to rebuild its machinery by solving puzzles and bring the world back to life by shaping sound and creating music within the game. FRACT features a beautiful open world to explore and decipher with music-based puzzles, stunning visuals, and an amazing score that evolves as you play. As you progress through the game, you unlock tools to make your own music in the FRACT studio, where you can also export and share your creations with others.

What are Phosfiend Systems’ greatest achievements and what is Richard the most proud of?

For a first game, it was pretty ambitious. It’s a big, weird game and it’s something we can all be really proud of. The reception was really good, the philosophical things we wanted to try and achieve I think got achieved, and the people that the game does resonate with, it resonates in the way we were hoping. I think in a lot of ways the game turned out the way we wanted it to, obviously with some compromises, of course, but I think the greatest success is just the reaction; seeing people make music, seeing people discover their musical side through it and seeing them have those ‘Aha!’ moments.

So, as is generally the case with games (any project, really) compromises were made in order to get FRACT to where it is today. Richard said that scaling down was difficult for them–you can always put more time into a game, but when is enough really enough? And how do you make that decision? For them, the bottom-line was about relevance and keeping their cool.

We easily could have worked on the game for another two years, but there was definitely a point of diminishing returns, both in terms of polish and visibility, so you know, we could have put more effort into aspects like features or polish, or… Just more of everything! But I think our sanity was kind of in danger of running out, I guess. There was also danger of people forgetting about it. If we took another six months, the landscape would have changed and there was a danger of it not being as relevant.

What were the greatest challenges Phosfiend Systems faced while developing FRACT? One common reason any team falls apart is miscommunication–Phosfiend Systems didn’t want that to happen and worked hard to make sure the lines of communication stayed open.

We were all new at this, none of us had ever done anything like this before, so I think just learning on your own dime is really stressful, especially since it’s such a small team and your victories are your victories and your mistakes hurt that much more. I think a big challenge was communication for us. We’re just a three-person team, so we had to learn how to communicate effectively between us and really appreciating everyone’s method of communication, that was the challenge. I think we did eventually nail it and we understood how to really communicate with each other and respect each other and really understand where everyone was coming from. We got there and it was really solid but that was definitely the struggle: learning about each other, learning how to interact with each other and learning what the project was; there was a lot of challenge there in just figuring it all out.

Why did the team apply for the incubator and how did it help them during early development of the game?

The incubator more than anything sounded like a great opportunity to meet people, [to do] something similar and to learn in that sort of environment, learn from other people … I think in some ways, we almost weren’t ready for some of the things that were given to us during the incubator because our design and our idea weren’t quite there; we were still looking for the game and we hadn’t found it at that point. The incubator served as a good playground for us to experiment and that was good. Pretty much everything we did during the incubator is gone, but I think that’s part of the process: iteration. And even though we were oblivious to the fact that that was what was going on, I think the incubator primed us for that understanding and that was good for us.

What advice would Richard give aspiring game developers? It’s an oldie but goldie:

Number one–and everyone says the same thing and we’ve heard everyone say the same thing and we thought we listened, but we didn’t–is to make it smaller; make everything a tenth of what you want it to be. [Once you] design it, you’ll find that only ten percent of it really matters–focus on that. We spend so much time designing ornate boxes and sometimes we forget that we have to fill them. I spent the last year and a half of FRACT development just filling the box that we built for ourselves, and that’s exhausting, and not necessarily what you want to be doing. And I know everyone in the industry, whether indie of AAA, says the same thing but if you can refine your idea or refine your experience into something smaller and gorgeous, I think it’ll be the better for it. It’s the same-old, same-old story, honestly. Look at Vlambeer, there’s an example. They make these hyper-polished but arguably very curated-kind of experiences–but they find what’s good and then polish the hell out of that, and well, look at how they’re doing.

Richard will be visiting this year’s participants at Critical Hit HQ on the afternoon of August 6th to speak on a panel of indie pros about production and marketing (or “what to do with your games once they’re finished”). We’re looking forward to having him back!

FRACT is available on Steam, GOG, HUMBLE and Indie Game Stand; you can also grab the soundtrack. Want to know more? Visit: http://fractgame.com/