(With the Curious Games Studio coming to an end, here’s my report on the creation of Nitrogen Narcosis – why it was made, what I found interesting and challenging, what my poor playtesters thought, and a bit more about myself than I usually talk about.)

I have been making video games since January 2013 and this is my third game. I never expected to be doing this – I thought that I might fall into video game writing somehow because video games are something that I enjoy and I like to try new things, but I didn’t expect that it would happen so soon, or that the urge to keep making more would hit so hard. The opportunities to keep making games keep coming. It started with the Pixelles Incubator – I applied but didn’t get in, and decided to do the follow-along program anyway.

While I was following along with Pixelles, I wanted to write an article about Global Game Jam 2013 – watching the participants, seeing what they were up to, maybe providing some suggestions or copy editing help while I was there – for the JEKA GAMES and the TAG blog. Less than twenty-four hours before this year’s Global Game Jam, I came into possession of a laptop that actually made it possible for me to help with the game making if I chose, and as soon as I was at the Jam listening in, the infectious energy of the whole affair was basically irresistible. I’m someone who likes to create; I’m moving next week, and I have four boxes of art supplies moving with me. After GGJ2013 and the Pixelles Follow-Along (and the Pixelles were extremely supportive and let me showcase my game along with the other participants), I heard about other opportunities to learn about games like the Curious Games studio, or my next project, a game for the Critical Hit Collaboratory. So, while I feel like a bit of an impostor (I had no training in making games at all up until the Curious Games course), as long as people keep giving me the chance to make games, I’m going to keep on making them – and if they ever stop, I’m still going to make them.

I wanted to participate in the Curious Games studio to hear about Pippin Barr’s approach to making games, because the current scope of my games is similar to the kind of games that he makes, and the games that he makes make me feel like I’m sharing in a great joke while all the while being teased a bit myself, and I like that. I wanted to make a game like that. But what to make?

I have already made a game about scuba diving – it’s one level, it’s what I developed in six weeks spending about six hours a week during a semester of grad school for the Pixelles Follow-Along, and the mechanic is basically that you swim around collecting points and will get more points by following diving safety rules like coming back with a certain amount of air in your tank. With that game, what I wanted to do was share a space that I love with other people (Morrison Quarry in Wakefield, Quebec) and learn the basics of using a game making tool and developing sound. I am also currently SSHRC-funded to write a master’s thesis in creative writing about coldwater Canadian diving. So, when I started to think about ideas for the Curious Games Studio and what kept coming back to me was a single experience that I had a few years ago, I wondered if I should really be making another game about diving. But then I thought, why the heck not? Cormac McCarthy wrote one book about cowboys in Texas, and he liked that so well that he wrote another one, and then another one (this is a poor paraphrase of something that Josip Novakovich says in his book on writing, Writing Fiction Step by Step).

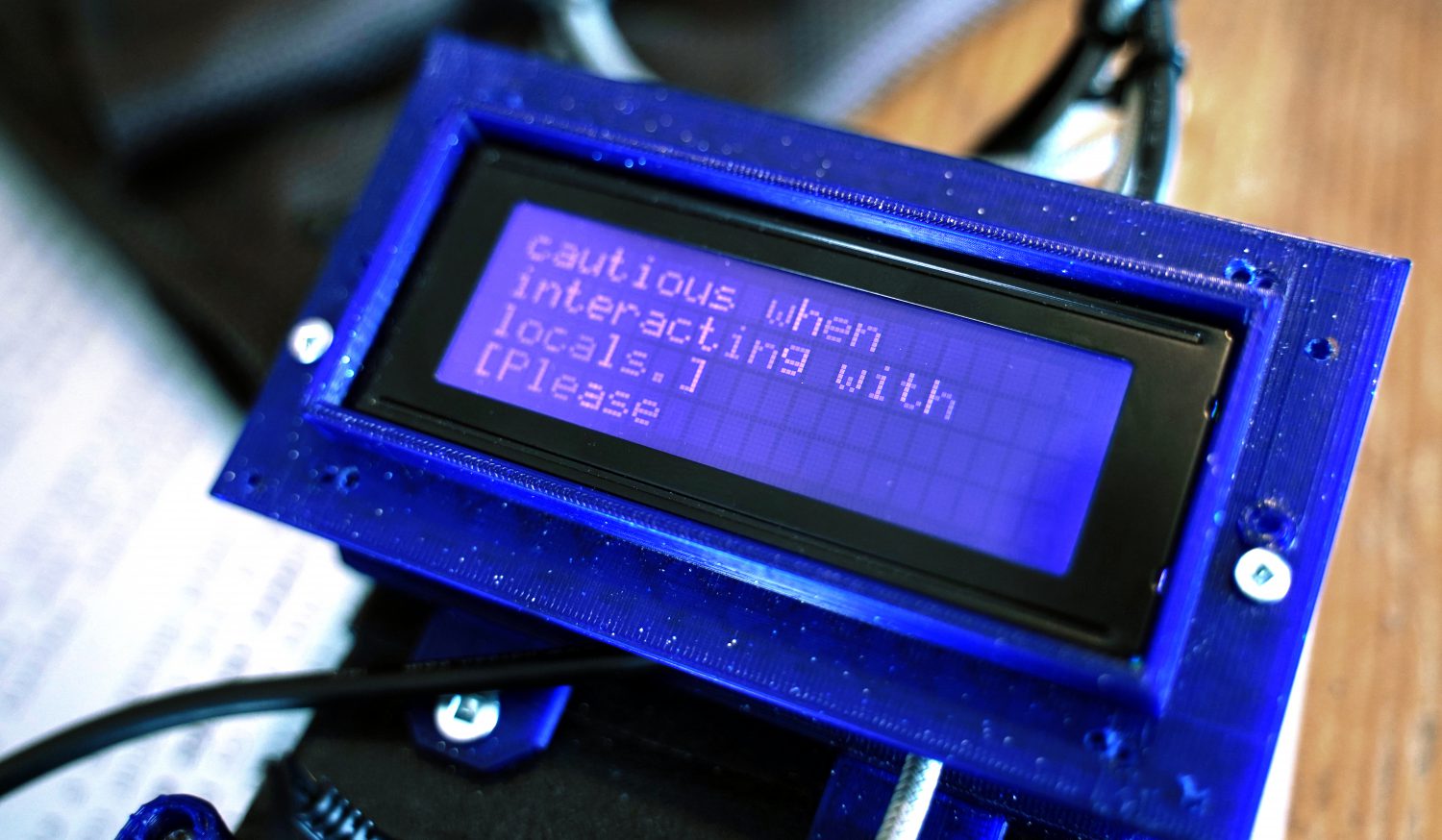

What I finally decided was that I wanted to impart an experience, and that what I had in mind was an experience that not many people are likely to have had. I thought that that was a good premise for a curious game. The experience in question is: “What it feels like to try to complete a simple task one hundred and thirty feet underwater.” The task is tic-tac-toe. The thing that I don’t mention in that description is that at 130 feet, most people are experiencing at least mild symptoms of nitrogen narcosis or are suffering other (mild) ill effects from the pressure and, in the case of coldwater divers in Canada, the cold. A person’s thoughts are slowed and their motor skills are adversively affected. So, the symptoms of Nitrogen Narcosis hit in the game at random in the form of those very dramatic scene changes. All these effects are compounded by my having the player wear some actual scuba gear – it doesn’t look like much, and personally I’m pretty well used to it, but scuba diving equipment is awkward and limits range of movement and dexterity very effectively.

The germ of the idea for tic-tac-toe specifically came out of my first experience with really deep diving. A deep dive in recreational scuba diving is any dive below sixty feet, which is the limit of the first level of certification. When I say “really” deep diving, I mean more than doubling that depth to 130 feet. As part of my deep diving certification, my instructors took me down to 120 feet or so and had me play tic-tac-toe against one of them. I didn’t get fully “narc’d” as we divers would say, but my ‘O’s looked pretty much like small outlines of continents. That my motor skills were so dramatically affected was a total shock to me, and that was part of what I wanted to transmit to the player. I would have loved to create some kind of interface like the one in YOU HAVE FORGOTTEN HOW TO USE A PEN, but I think that if I had tried that might have been the only thing that I managed to finish, and this was a game about being immersed in an underwater environment.

What I find interesting about Nitrogen Narcosis is how well the seemingly trivial aspects of the game such as the user-enforced rules of wearing scuba equipment and actually following the rules for playing tic-tac-toe lend themselves to the game experience. What I couldn’t do with programming, actually slowing a player’s movements down with the mouse on screen, or really creating feelings of confusion, the scuba equipment achieves. The mask fogs up on the player’s face, and the thick neoprene gloves make the keyboard keys much more difficult to press, the buttons on the mouse more likely to be mispressed or the mouse directed to an area of the screen that the player wasn’t aiming for.

I also find it interesting that even after working on it for the duration of the class, I still have a lot of fun playing the game, even though I must have playtested it hundreds of times in all its various stages – although of course this is partially the delight of seeing my work, well, work! Even more interesting is that the late addition of the two-player mode is what really makes Nitrogen Narcosis feel like a finished game. It creates a collaborative (or maybe adversarial) aspect to the gameplay and really highlights the ways in which this simple task is made more difficult by the gameplay aspects. Player One, who places the ‘O’s, only needs the nine keys that correspond to the nine spaces on the tic-tac-toe board, and they’re not forced to wear anything. That means that the general reaction from most of my Player Twos was a good-natured “hey, how come I have to wear this and they don’t?” which enforces the idea that this is no simple game of tic-tac-toe right from the get-go.

Some schools of creators (like the OULIPO artists and writers) say that constraints are great for creativity. Nitrogen Narcosis is a game that proved that to me because I had plenty of constraints: I am not a programmer, I’m not a professional 3D or even 2D artist (the farthest I get is graphic design in Photoshop and maybe “inking” my scanned drawings), and I only had eight weeks to make the game. To be fair, I do have a bit of fine arts background, having taken a DEC in Communications: Arts, Media and Theatre in CEGEP, which is basically a program where they let you paint, draw, sculpt, take photographs, and make movies while they also teach you about journalism and cultural studies, but I have no idea how to use Maya or Blender or any of those tools. At the core, I’m a writer who dabbles in other mediums. I also decided that it wasn’t the time to learn to use a modeling program, especially since I don’t know which one to use, so I resolved to make art that I could draw using my fingers in Photoshop on the trackpad. There is something really satisfying about this kind of art – it’s something like fingerpainting and it makes me appreciate the existence of each asset as I have painstakingly taken the time to draw it – and the trackpad on a Mac draws way better than I ever would have expected it to.

The immediate repercussions of my relative inexperience were that I had to find simple ways to get the effects that I wanted and that I had to feel my way through the programming parts of anything and everything that I wanted to put in the game. This forced me to think about the challenges of the game in different ways. Even as late as our last class’ worth of studio time, I added the multiplayer mode and was both delighted to find that I had reached a point where the programming (although it is visual programming in Stencyl) came easy and that the two-player mode added dimensions to the game that I never would have expected.

Initially, I had wanted to program an AI to play tic-tac-toe against the player, but this proved too difficult and, as it turns out, this was a blessing since it resulted in the eventual addition of a two-player mode, which I feel really makes the game feel complete. Programming a tic-tac-toe AI was more complicated than we had realized, and with the added difficulty of fighting the Stencyl interface, I decided instead to try having the player play against themself. This is how the game remained for quite a while until we playtested again and decided that there was some missing impetus – some missing motivation to take the player through five sections of playing tic-tac-toe, especially against themselves, even if interesting things were happening all around them.

Another feature that I wanted to implement but wasn’t able to was actually making the perspective/player move up and down when the player “controlled their buoyancy” by pressing the blue and black buttons. An artefact of this is that both of those buttons still make appropriate noises if pressed on – but only one of my playtesters pressed on them and they were a scuba diver. I find this artefact interesting and decided to leave it in because of one of the discussions that we had in class about human/player psychology: that we have a strange belief in buttons – that we believe in their power to create agency for us out in the world. Apparently, in some countries, the close elevator door buttons don’t actually work (although at least the ones in the EV building at Concordia where the Curious Games Studio met seemed to work).

A major challenge for me was debugging. I tried to be as methodical as possible, but oftentimes I couldn’t tell the difference between a bug that Stencyl had created because it generates code and has some flaws and something that I had actually introduced with my code. Sometimes, I couldn’t get the bugs to reproduce, and often times, if it was a Stencyl problem and not a Jeka problem, I basically had to “rewrite” that section with the exact same stuff that had been in it before. Additionally, towards the end of the process while I was fine-tuning something, the graphics card in my laptop took sick (I can’t exactly say that it died because it still works in fits and spurts). I thought that I had a bug that was crashing the game, but it turned out that it was the graphics’ card. This could have been disastrous: for a few hours I was completely unable to turn on the laptop. Thankfully, I was finally able to turn it on long enough to back up everything related to the game. It was a scary moment – the kind that you hear about. So, that laptop that got me started on making games all those months ago basically died for me to make this game.

One of the resolved challenges that I feel particularly good about with this game is randomization, which I managed to learn how to do within a range of numbers in order to have some events occur at random – particularly events within the different scenes and the scene changes themselves. I wanted the game to have an element of the unexpected every time a person played. The end result is not that varied, but I think that it’s better than having static scene changes and totally scripted events. I am also pretty satisfied with the sound design – the breathing noises, freeflow noises, and button-press noises are all things that I made myself in Audacity using resources from Freesound.Org, and I was surprised that they actually sound comparable to similar sounds in a prototype that I discovered yesterday for the Oculus Rift, World of Diving (honestly, I hope that this prototype changes drastically because I’d love to play it but it’s clearly meant to be a simulation and already there are many things wrong with it from my perspective as a diver – for example, that diving is largely about planning, so you’d never carry around all those pieces of equipment with you, and that buoyancy control is something you usually really need to pay attention to).

One thing that I’m still not sure that I have one hundred percent right is the timing of those scripted events – as I’ll discuss later, it’s a problem that I ran up against in playtesting.

The greatest influences that I can identify for the overall perspective and look in this game are the Doom and Wolfenstein interfaces. I’m talking about the combination of that perspective with the art style of the assets. In terms of tic-tac-toe gameplay, I wanted to mimic the interface of those older PC versions of Chess with the flat board and flat pieces. It was also important to me that, as in many FPS, you be able to see parts of your equipment to give you a sense of perspective. Other influences, especially in regards to actually making the player wear or use equipment while playing are games like Hit Me!, Painstation, Propinquity, and the Wii, where the physical world that the player inhabits has in-game effects. In Hit Me!, for example, the size of your opponent relative to you affects how easily you’ll be able to reach them (I found out just what an impact this has on gameplay by playing Hit Me! with my 6’ 5” friend Jordan).

I playtested the finalized (well, sort of finalized) version of the game on two separate formal occasions. The first time, I asked my fiancé Tom and my friend Colin (from Red Rings of Redemption) to test it. Tom is an experienced scuba diver – he even introduced me to the sport and has been listening to me talk about the development of the game since I started on it. Colin had heard a bit about the game, but didn’t have any real idea what to expect.

On the first playthrough, Tom took the role of the first player, or the person who only has to press nine keys and doesn’t have to wear scuba equipment, and Colin graciously accepted to wear scuba mask and gloves, although he drew the line at putting the snorkel in his mouth (this is not one of the requirements to play Nitrogen Narcosis). The result was almost utter chaos: in every level, they seemed to hit the random events – particularly the scene changes on the lower end of the time ranges for the randomization. Scarcely had they touched their tiles did it seem that the scene was changing and they were on to some relatively wild stuff. The effect created was a kind of confusion – which is kind of nitrogen narcosis-like – but it was not the desired sort of confusion, really. On a second playthrough, with each of them knowing what to expect and with Tom now playing the role of “person with loads of equipment in their way”, things went more smoothly. They did find a few physics bugs for me which then mysteriously fixed themselves (or rather, I haven’t been able to reproduce them).

Colin’s suggestion was that maybe the game should provide more explanation about what nitrogen narcosis is, but I decided that this was not what I wanted for the game. For me, the context of having to wear scuba equipment and hearing underwater breathing noises, seeing fish, suggests that Nitrogen Narcosis, which is the game title and even sounds like a medical condition, is some kind of scuba-diving related affliction.

Both of them suggested (and I observed for myself) that things were happening a little too fast. So, the upshot of this playtest is that I adjusted the time intervals for the random events and scene transition, and debugged a little further.

The next day is when my laptop graphics card started to really give up the ghost, so I spent a few hours over the next two days assuring myself that I had managed to back everything up and that I could still alter the files from another computer.

After that, I playtested with my parents, Michael and Judy. Michael’s reaction was to initially refuse to wear any scuba diving equipment at all, so I suggested that he start as Player One and decided to try and change his mind later.

Judy, starting as Player Two, was a pretty good sport but griped about my father not having to wear anything. Now, my parents can be described as casual gamers at best – they play Angry Birds on my father’s Kindle and maybe a few other similar touchscreen games. With them, the game seemed to hit all the right notes. Although my mom told me halfway through the first game that, “personally, [she didn’t] care for this at all,” she then went on to play two more games, complete with trashtalking my father and cheating (they both cheated a little bit when they realized that the tic-tac-toe rules are completely player-enforced). My father suggested that the “taking turns” rule of tic-tac-toe should be enforced with programming, but I so appreciated the generative play of them each trying to play faster than the other and moving each other’s pieces around that I definitely think this should stay as is. When they were exploiting the loopholes and player-enforced rules, they seemed to be having the most fun.

When it came my father’s turn to be the ‘X’s, I could only convince him to wear the neoprene gloves. Throughout the game, he became so frustrated with the way that they limited his motor skills that he actually tore the gloves off. My father is one of my “constant readers” – I basically have him check out nearly everything that I create, and so he is skilled at stepping back from himself and giving me a considered perspective even of things that he doesn’t necessarily enjoy. His main reaction was, “I see what you’re trying to do here, and I think that it works. I just don’t want to wear those gloves again.”

After their playtest, I tweaked the positioning of the ‘X’s so that they all start in a pile on the side rather than scattered on the board – this had caused some confusion for my parents, since one of the rules of tic-tac-toe is that you can’t place your piece on a square with someone else’s pieces, and the ‘X’s start in certain positions. If the player is trying to follow the rules to the letter, that’s a legitimate concern. It was simple to change so I decided to do so.

Overall, the playtesting experience was positive and very constructive. I’m looking forward to see what people who don’t know me think of Nitrogen Narcosis. Creating the game has given me a much better handle on Stencyl and I’ve learned quite a few new tricks. It feels good to have finished this game – I think that I’ll lay off the scuba diving games for a while.

(I’ll be posting the game online soon, along with a possible list of alternate equipment for those players who don’t own their own scuba equipment.)