TAG Profiles is a blog series that explores the work of current TAG scholars. Skot Deeming is a doctoral candidate in Concordia’s Individualized (INDI) program, as well as an artist and curator.

TAG Profiles is a blog series that explores the work of current TAG scholars. Skot Deeming is a doctoral candidate in Concordia’s Individualized (INDI) program, as well as an artist and curator.

Could you give me a brief overview of your doctoral research?

My research focuses on toys in the late twentieth century and early twentieth century. I’ve been charting the rise of the action figure as a cultural form and how, in the mid-2000s, it mutates into its own artform through designer vinyl toys and bootleg art toys. The trajectory of my research is essentially: how do we get from a mass-produced branded childhood play thing in the 80s (such as GI Joe and He-Man) to a largely appropriation-based art scene in the present.

When looking at the phenomenon of branded and franchise toys, you have to start with Star Wars. It was the franchise that really solidified licensed properties as viable toy lines. Previous to that, most toys were either original properties — perhaps most famously Barbie and GI Joe — with the exception of some licensed toys based on TV brands. Star Wars was a licensing sea change as it was the first time that a movie license absolutely exploded. Ultimately, the phenomenon changed the ways that kids play through the rise of transmedia marketing.

GI Joe is a good example of this transformation. It started as a toy line in the sixties, fell out of favour in the seventies, and finally made a comeback in the eighties, gaining traction because of a tie-in Marvel comic and an after school cartoon. In the eighties, if you wanted to have a successful toy line, you also had to have a successful comic book or cartoon to coincide with it. Mark Steinberg writes about this in terms of the Japanese media-mix, in which toys are an integrated medium in terms of the way they are concerned. In North America, the trend begins with Star Wars and catches fire in the eighties with Reagan, who deregulated childhood television programming and enabled the half-hour-long cartoon/commercial format for toy lines. Transformers, Thundercats, and He-Man all sprung forth from this change. Every toy line had a corresponding cartoon and I use that phenomenon as a template for where we are now.

How does that move us toward the art-based practice that you spoke of earlier?

The trunk of the tree is made of particular IPs and licenses and the branches are how they established an industrial norm, but also where and how critical interventions and appropriation enter the game — in the bootleg, art toy, vinyl designer toy scenes. One of the reasons I’m writing on this topic is because I am a participant in these scenes, so I am intrigued by their histories. I’m very interested in the intersecting cultural currents that led to their emergence.

|

|

|

How do you participate in the practice?

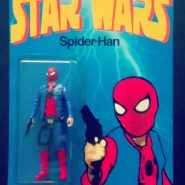

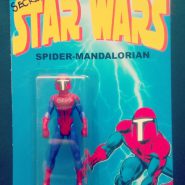

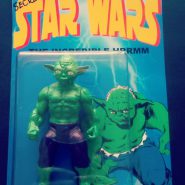

I spend most of my time these days either working on my dissertation or making custom and bootleg art toys. It may be more like three quarters making toys and one quarter writing right now (laughs), so maybe I need to develop some better writing habits. Making a bootleg toy usually starts with some weird, esoteric idea. The scene is predicated on mashup culture — so, you take “brand x” and “brand y” and stick them together to get a new thing. As an example, I recently created a triptych of three action figures that were mashups of Marvel comics and Star Wars characters. I made Spider-Han Solo, the Spider-Mandalorian, and a Yoda Incredible Hulk that I called the Incredible Hrrmm (Yoda thinking noise). Those are just the figures, but the form also includes the packaging, which was a mashup of vintage Star Wars packaging mixed with Mattel’s Secret Wars packaging from the eighties. I called it Secret Star Wars.

Although it can often turn into a political or intellectual exercise — for example, I recently did some work inspired by the US-Iran conflict featuring vintage 1990s Desert Storm trading cards — a lot of it is instinctive and a type of found materials practice. I literally have a bin of toys and parts and it’s a matter of putting things together like a puzzle. Or sometimes I have an idea and I think “I need the head from this action figure and body from this action figure” and the result is a strange hybrid. I recently made one called C3Devo and it looks like C3PO but he’s dressed like the band Devo. Maybe “intuitive” is a good word for it… thrifting for parts and looking through bags of action figures to seek out inspiration.

How do you showcase these toys; where do they live?

They live mostly on my Instagram page, which is one of the main ways the scene disseminates itself. There are galleries, comic-cons, and collector’s conventions, but day-to-day everyone just posts their stuff on Instagram. It’s the first time that I’ve been involved in a scene that was so platform-specific. I suppose it is because of its visual focus and the indexically of hashtags. Whenever I finish a work, I post it inn my store then upload a photo to Instagram.

Where can people find you online?

You can view an archive of my past work at Yoyodynetoys.tumblr.com, and my current work is available at Yoyodunetoys.storeenvy.com. You can also follow me on Instagram at yoyodynetoyz.