I recently read through Sebastian Möring’s excellent article “The Metaphor-Simulation Paradox in the Study of Computer Games” (2013), and it got me to thinking about how easily discussions of analytic and ontological frameworks bleed into each other (not to accuse of Möring of this – more on that later).

Möring’s argument starts from three observations: 1. that the concepts of simulation and metaphor are often used in textual and conceptual proximity to each other, 2. “metaphor” is often used to “signify seemingly abstract games in opposition to mimetic simulations,” and 3. that the definitions for metaphor and simulation are too similar to be usefully distinct.

In support of these observations Möring shows how game scholars (myself included) have traditionally distinguished games-as-simulations from games-as-metaphors. His key insight is that both of these categories (without going into too much detail) hinge on representation via abstraction and reduction, in other words, that both simulations and metaphors are inherently synecdochic. Ultimately, Möring argues, the distinction between the two is meaningless because they are essentially the same thing. More specifically, he argues that all games can be simulations because the designer or player can always interpret a game as a representation of a system of some kind.

This is of course a bit of a simplification of his argument, but should be a sufficient basis for what I want to talk about here.

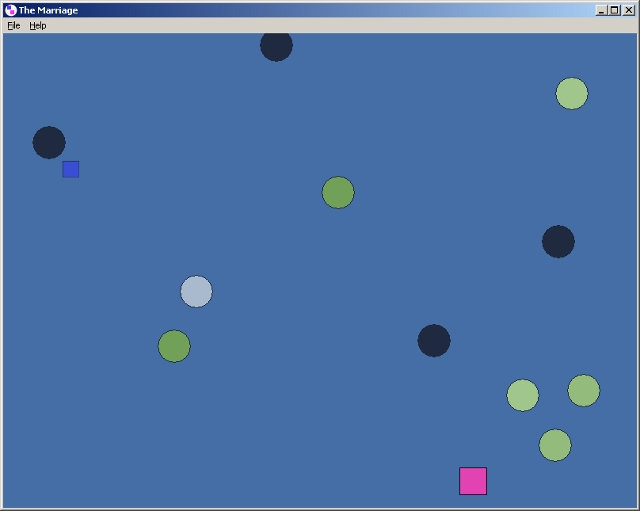

In my work on simulations and metaphors I argued that a simulation is a representational system based on a source system that communicates that basis to its user: in this framework SimCity is a simulation because I know that it’s simulating urban development (or more specifically the model of urban development outlined in Jay Wright Forrester’s book “Urban Dynamics”). For the same reason The Marriage (pictured below) is a simulation because the title informs the user that it is simulating marriage. I used the term “metaphor” (based on Lakoff and Johnson’s seminal “Metaphors We Live By,” 1980) to describe games that were not explicitly simulating something, but that the user could ascribe such representational status to.

This kind of ontological distinction, however, is precisely what Möring is arguing against, very convincingly in fact. At the same time, I think my distinction is quite workable and useful.

The difference, of course, between these two positions is that Möring’s framework is ontological, whereas mine is analytical (not that Möring claims otherwise).

This distinction is, in hindsight, completely obvious, but to be honest it did make me some time to arrive at it. And I think the reason for my own conceptual delay is that this kind of slippage happens all the time in academic discourse as discussions about “what something is” blend into discussions about “how we can conceive of something.”

As another example, consider Jesper Juul‘s well-known dualistic ontology of games as Half-Real: part rules, part fiction (2005). Although Juul presents this an ontology I have often found it useful to think of it more as an analytic framework. The reason for this is that if an ontology is problematic it can quickly become a conceptual block: how can we use ontology A if it doesn’t account for factors 1 and 2? I am not sure the spatial aspect of games fits into Juul’s ontology, for example. As an analytic framework, however, I find it invaluable to be able to consider games as combinations of rules and fiction and to be able to isolate and analyze those particular aspects. But doing this depends on changing perspective on said framework. Because we expect ontologies to be precise, exacting and complete it is nearly always possible to poke holes in them. Arguing for the value of an analytic framework to somebody who is conceptualizing said framework as an ontological one is not going to work very well, because from an ontological standpoint the framework will nearly always be incomplete or problematic.

This semester many of us TAG-sters are participating in Mia Consalvo‘s “Critical Game Design” course, which examines how social, technological and industrial practices shape game design. The course is approaching its end and yet nearly every week we return to the problem of defining “platform” (in a platform studies sense), which leads to questions of materiality, which in turn leads to problematizing the whole hardware/software distinction (because ultimately all matter and energy are the same thing anyway). Thus the ontological questions interfere with analytic questions: although the code for Radiant Silvergun is ultimately the same thing as the Sega Saturn running that code, it is occasionally useful to be able to distinguish between these two things. In terms of platform studies, while it can be nigh impossible to pinpoint where exactly a platform begins and ends, it is often useful and productive to establish those points for the sake of moving forward. Thus the endless utility and power of the phrase “for the purposes of this paper…”

It is thus important to distinguish analytical frameworks from ontological and to be wary of slippage. It may be entirely incorrect to say that “thing X is composed of parts 1, 2, and 3,” but at the same time entirely useful and productive to be able to talk about parts 1, 2, and 3 and how they work in thing X.

As an example from my current project on train games, before reading Möring’s paper I had been working with a distinction between what I had conceptualized as “simulation” train games and “themed” train games. In the former I was including complex games that were expressly trying to recreate some aspect of the railroads, such as 1846 or Silverton, while the latter referred to games where the train fiction was not expressly implemented in the rules, such as Ticket to Ride and Mexican Train dominoes. What Möring’s work shows is how that distinction is flawed as an ontology. But as an analytic framework it is useful to be able to distinguish between these types of games because they reflect different modes of engagement with their subject matter, even if both should be properly considered simulations.

To return to the analytic vs. ontological framework argument, I anticipate that one objection could be that ontology is interested in the Truth of a thing, whereas the pragmatic approach of analytical frameworks I have advocated for here is interested more in enabling new questions and less in the Truth. This is a fair point that is hard to address without diving into epistemological questions. As such, for the purposes of this blog post I will assume that Truth is always already subjective anyway.

Works Cited:

Begy, Jason. Experiential Metaphors in Abstract Games. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, vol 1. no. 1, 2013.

Juul, Jesper. Half-Real. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005.

Lakoff, George, and Johnson, Mark. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Moring, Sebastian. The Metaphor-Simulation Paradox in the Study of Computer Games. Internatinoal Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations, 5(4), 48-74, October-December 2013.