You are handed an envelope and instructed to text “READY” to an unknown number. You send the message and look through the envelope. In it is a single loonie, which you pocket. You receive a text and image from the number: “Follow this handrail to the auditorium. Walk slowly. Text me the room number at the end.”

You follow the instructions, guided by a series of texts and images from the unknown number. You are told you are looking for someone named Lucie, someone who has been missing for a long time.

You are told to “keep your face hidden from the cameras.” You look up to try and see the cameras. You are not sure whether you are more engaged by the mission prescribed to you, or the fact that you enjoy playing the role.

In early April, during the height of end-of-term madness, over twenty students, faculty, and artists gathered at Concordia to kick off a week of workshopping, making, and conceptualizing. The week was part of an ongoing collaboration between independent theatre and digital art company ZU-UK and Milieux’s Technoculture, Art, and Games (TAG) lab.

The starting goals for the week were vague, but exploratory: the group would break into teams and then make projects based on a similar set of concerns. The projects all needed to consider and make something based on the terms “participatory, public, locative, performative, and game.”

The ongoing tension of the week was between making things and contextualizing them.

How do we determine how much time to spend on each part of the process? At what point is it necessary to physically experiment with what has been conceptualized, and how often is it important to go back to the conceptual drawing board?

You receive another text: “There is a coffee cup in one of the plant pots. I left instructions inside. Do EXACTLY as it says.” You find the coffee cup and ignore the weird looks from the strangers watching you as you pick the instructions out of the cup: “Buy the cheapest thing in the cafe.” You follow through, purchase a banana, make small chat with the barista, try to appear natural. But your phone buzzes again, another text. It is a picture of you, followed by another message: “You have been compromised.”

There is no singular kind of process in group collaboration, rather an ongoing entanglement of making and reflecting on that making. But what seems to work best is an ongoing process of making and reflecting–with neither part of the process dominating the other. Maintaining singular and specific goals is also necessary. Because the week was an experiment, everyone came with different expectations for what was inevitably not-quite-game-jam, not-quite-conference, not-quite-makeathon. By defining the process through nots, we are able to narrow the focus. It is often the simplest, most constrictive goals that allow for the most bizarre, interpretive possibilities. Interactive experiences are similar. Participants need to be drawn in with the least amount of explanation possible. They need to understand their role immediately. They do not necessarily need to feel safe, but if there is a leap, they need the incentive to jump.

How we frame playable experiences is similar to how we frame these collaborative processes.

Someone comes up to you. You don’t know them. “You just missed her,” they say, and hand you a pair of headphones.

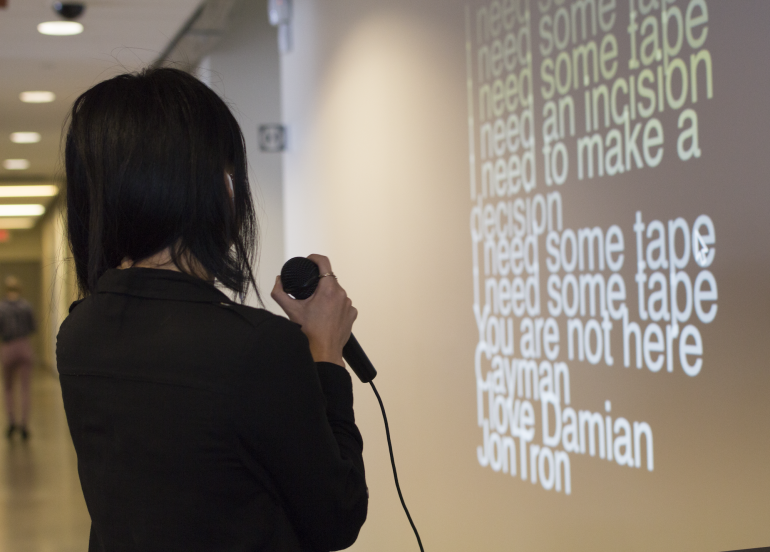

You put the headphones on and hear a voice. It is the voice of Lucie, the woman you have been looking for. “I don’t want to be found,” she tells you.

She instructs you to look up, towards the top of the staircase. You see another person, in your old footsteps, picking up an envelope as you once did. You follow them from a distance, listening to the voice. You sabotage their progress, take a picture of them standing outside the cafe.

You realize you are the cameras.

In making, thinking, and experimenting, we must remain aware of how our actions function. How do we invite all participants to feel welcoming in our critiques? What conversations are we participating in by conceptualizing? When are we just following prescribed instructions? How do we make our making matter?

When we take part in engaged critique, we embrace the discomfort of unknowing in order to find something new.

“Sometimes it is important to stay with the trouble,” TAG co-founder Lynn Hughes tells me, referencing the title of Donna Haraway’s most recent book. And maybe the reference is not so far off from what we try to do when we get together to critically collaborate. This act of participatory, critical collaboration is like a game of cat’s cradle, “passing on in twists and skeins that require passion and action, holding still and moving, anchoring and launching.”

You see them buying a banana, as you once did. You walk towards them, tap them on the shoulder, and repeat: “You just missed her.”

You have finished the game. (The not-quite-a-game.) And you feel like not-quite-yourself. You have participated in something much more cyclical and knotted than just an individual experience. You have entangled yourself with other participants in an ongoing process of “becoming-with-each-other” and now you are left looking–not for Lucie–but for your own relation and engagement with that complex, participatory web.

Note: There were a lot of amazing pieces created throughout the week that I wasn’t able to explore in detail here. For more photo documentation of these projects, see TAG’s Flickr here.

This piece was originally posted on Pause Button.