This is an excerpt. For a full version, click here to read it.

By Monday, I managed to relearn everything I thought I knew about Minecraft. The PC controls weren’t far from what kicks in for most folks who haven’t biked in a long while, nor was the in-your-face IMAX view I now had of a world I once stored in my pockets and iPad 2 cases when they were still trendy.

No, it was that this was Modded Minecraft— two words that continue to haunt players old and new. Not to mention, all 217 mods lived alongside everyone here at TAG whose key impressions of me were getting “Bested by a Tiger”, dying shieldless by skeletons, and getting pancaked by a train from hell (sorry, Bart) in hell.

It didn’t take me long to realize how much work was put into their play.

Bart Simon, my neighbour/locomotive-enthusiast bourgeois of “Earth Cross”/a.k.a. the co-founder of TAG and director of the Milieux Institute, once asked why video games were treated so seriously? For a newbie, this was my exact thought. Everyone had immaculate builds and tools, materials of which I have never heard of or thought was capable in a game like Minecraft.

Why was there so much effort put into these digital livelihoods?

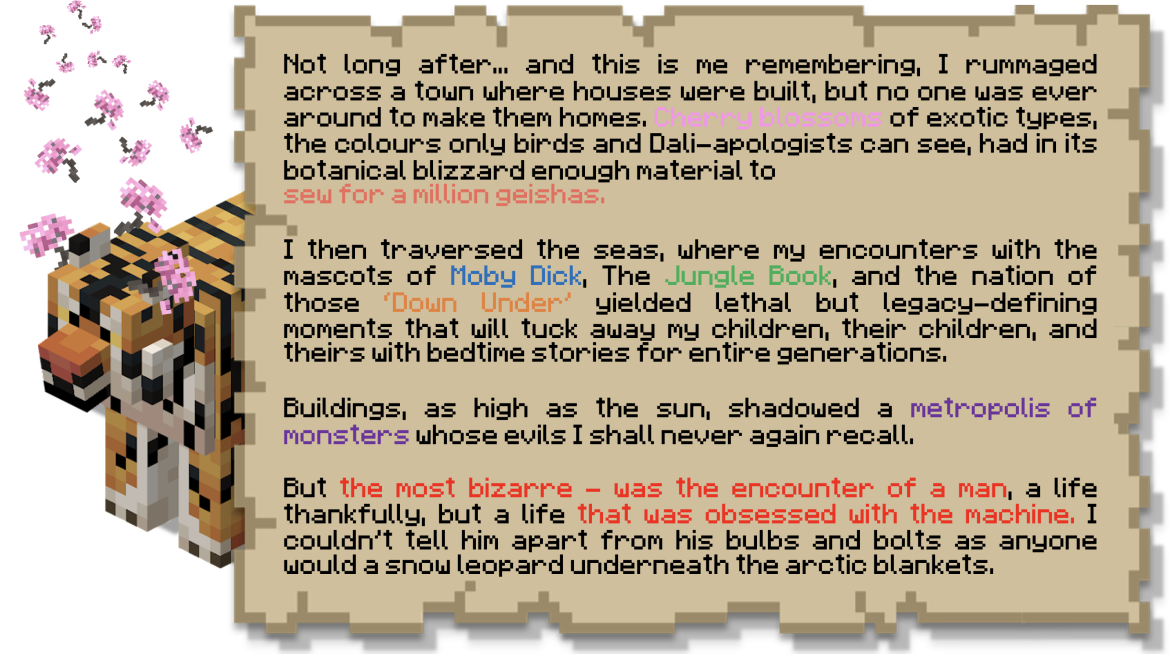

So many things resembled the real world: a boba tea shop, a train station, a forest of cherry blossoms. Sure, there were some stretched-out revisions, like these deadly things called Spellbreakers, or a hidden fried chicken shop that beheads chickens and every single piece of writing on morals for the sake of modernity and munching on good grub.

Fig. 1 Places of the World

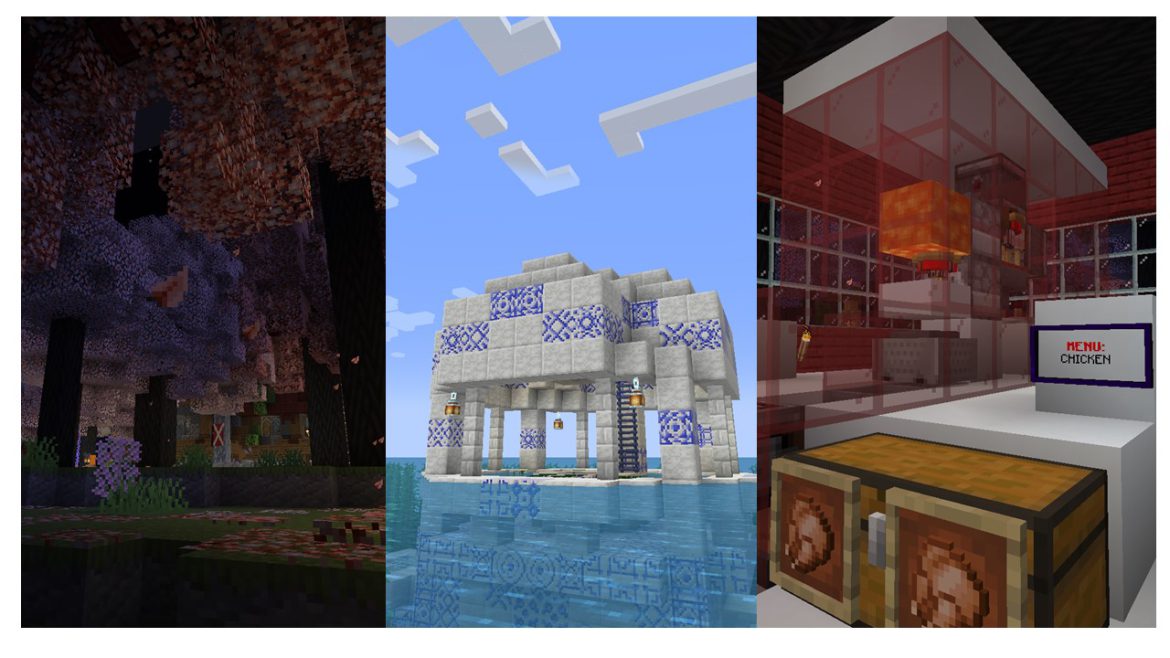

Fig. 2 The Dangerous – Big Zombo, Spellbreakers, and amongst them, Kangaroos

It was an equal measure of abstraction and simplification of life, which Coleman (1966) argues is what games are. With one death after the other, it dawned on me how difficult it was to just live normally. I started to miss the constant I had on MC Vanilla (though no longer Pocket Edition); where cherry blossoms don’t grow, tasks aren’t automated by titanic machines and where tigers, sweet berry bushes, and kangaroos aren’t all so deadly.

I was dying to live a normal game life.

So I quit. Went onto singleplayer survival and hit ‘play’.

20 minutes later, I felt like this was Pocket Edition, that this was ‘just not it’. That there was something missing.

What was it? The Nether? The End? I hopped on creative, traversed through these realms with enough kit from /gamemode (creative) to fight unscathed til the credits rolled.

Something was still off.

I am reminded of Anyanwu (1998), who spoke of technology as a rite of passage for humans, that:

In an “attempt at humanising a machine… [have we forgotten] what happens to the human that is being mechanised?” (p. 158)

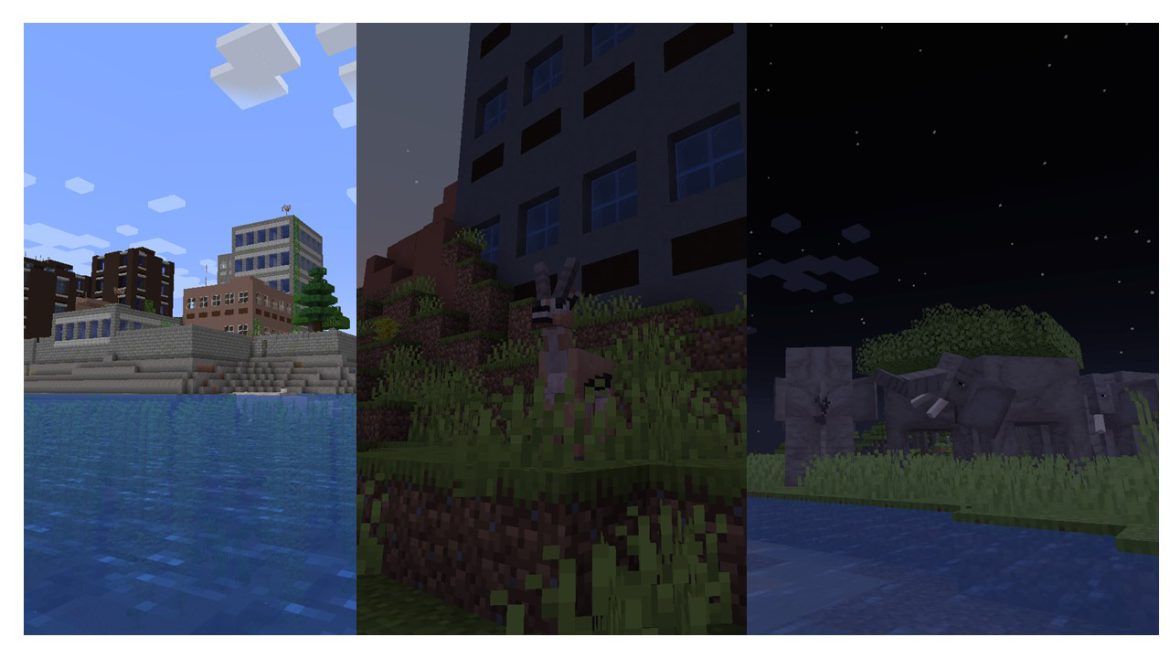

Fig. 3 Humans and Machines

Those damn tigers, the magic train, the engineering and architecture — these were machines that humanized Minecraft, but it also Minecraft-ed the human in me. I was marching to things, not walking amongst them; exploiting the villagers, not exploring their culture and communities; thinking of mobs nearby, and not sleep. Gosh, nights were the worst. What happened to the person – the sociologist, the newbie called Richy? I was bionasard, deadset to grind, grill, and game.

It wasn’t playing anymore. It was paying, for everything you’ve ever wanted.

After so many runs, it didn’t matter what desert temples, snowy villages, or shipwrecks I came to find. I was living as a machine: going through the routine, tutorials, and grind that millions of YouTubers have paved back and beyond.

Except when I did the same on the TAG server, something fulfilled me.

I grinded a home, some armor, left over a dozen creeper craters, and died shamelessly.

Fig. 4 Nature finds a way

I didn’t keep coming back because modded minecraft resembled so much of life and what could be, it was that I had become something with the life I’ve died over and over to define.

Dying with all these mods helped me to see what it meant to live in this reality – definitions of livelihood that every citizen of the TAG server died to define, and live to defy. It’s like Simon’s comment on social media (2009), where modded Minecraft gives to the life of its players who may:

“…need anything, [which] is the capacity to make familiar things like friendship strange, and therefore more relevant than ever before”. (16:00-16:10)

Yes, modded Minecraft is challenging. It takes the effort of Anyanwu’s (1998) humans that are mechanized into playing for a better life. But they are not machines, nor forgotten.

If it is meant to be challenging, then it is because its strangeness requires the familiarity of classmates, game-night groups, and MC communities. Life is the game. Not the other way round. We come to video games to die, to complain, to celebrate, but these things are lived amongst and with those who we share livelihoods with.

For it isn’t a life of playing that has people coming back for more,

it is playing for a better life.

Read the full story here.