Like many scholars from TAG, I had the privilege of visiting the Prairies last month to attend the annual Congress of the Social Sciences and Humanities. However, unlike the rest of Concordia’s contingent, I did not apply through the Canadian Game Studies Association (CGSA). Lured by the prospect of poster presentations and digital demonstrations, I joined forces with the Canadian Society for Digital Humanities (CSDH), where I presented my prototype ludomusicological database GameSound. While I was there, I took the opportunity to learn more about the sprawling field of the digital humanities – something that I first encountered through an aptly titled Digital Humanities course at McGill – particularly how it intersects with game studies, research-creation, and digital scholarship.

What does it mean to engage with the digital humanities? I’m generally not a fan of distilling complex fields of study into simple definitions, but perhaps a quick summary is in order to contextualize the rest of this blog post. The digital humanities is often regarded as an interdisciplinary field that examines how digital tools and methods can be applied within a variety of humanities disciplines. These tools can take the form of databases, search algorithms, data visualizations, and a whole slew of other software based methods. Although most commonly used for research in literature, history and philosophy, I am particularly intrigued with the overlap between the digital humanities and game studies.

Fortunately for me, the crossover between these two fields was prominently on display at this year’s Congress. One theme that weaved its way through the presentations was the idea of isolating and extracting specific video game assets in order to facilitate quantitative analysis and distant reading. By reducing video games to their component parts – sound, script, code, etc – scholars can make them accessible for new types of research. This approach treats the game as a sort of text: one that can be examined using tools originally designed for text-based works such as novels and manuscripts.

Jason Bradshaw brought this type of analysis to the forefront with his presentation BioShock Infinite and Feminist Theory: A Technical Approach. Bradshaw collaborated with fan communities to acquire a complete written script (nearly 250,000 words!) from the video game BioShock: Infinite, which then served as the corpus for his project. Influenced by a close reading of the game by Caitlyn Origitano, who analysed the representation of female protagonist Elizabeth, Bradshaw wanted to demonstrate how distant reading could corroborate Origitano’s qualitative analysis. The game’s script was fed into Voyant Tools, a popular piece of textual analysis software, to determine the frequency of certain words and where they occurred in the game’s timeline. Bradshaw tracked how Elizabeth was referred to throughout the game (paying keen attention to labels such as “baby” or “child”) as well as how she was treated by other characters, resulting in a measured, textual character arc. Although by no means an authoritative take on the game’s narrative, the study demonstrates a new methodological approach for game studies: one that invites complementary quantitative analysis using methods generally reserved for literary works.

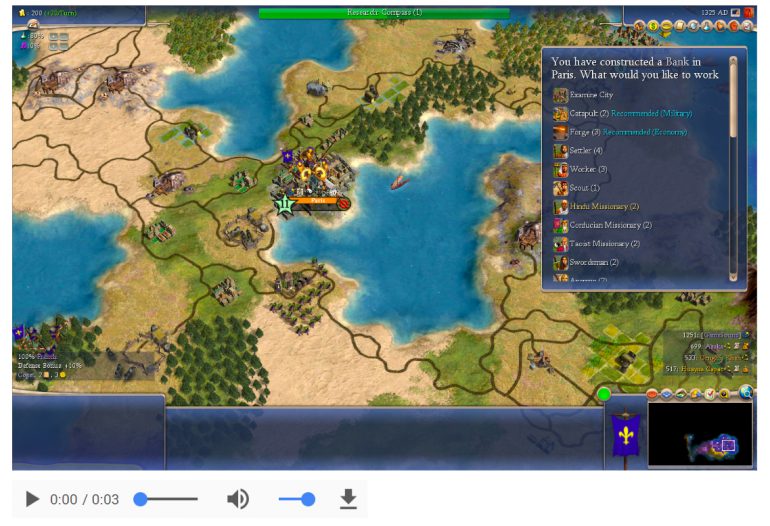

My own Congress presentation, GameSound: A Prototype Ludomusicological Database, also took a deconstructive approach, albeit with vastly different subject matter. Containing over 2000 audio files extracted from a Windows installation of Civilization IV, GameSound’s database enables point-and-click access to all the music, sound effects, and ambient tracks present within the game. By putting an emphasis on searchability – and utilizing a variety of both technical and ludological descriptors – the database aims to facilitate access to a game’s audio elements without having to rely solely on playthroughs or fan-created resources. Much like Bradshaw’s work, once the heavy lifting of data input and formatting is complete, data analysis can be customized and executed fairly rapidly. GameSound users are free to tweak visualizations, create custom reports, and even embed content on the web for easy collaboration and knowledge dissemination. This approach allows for quantitative methods that can be used in conjunction with qualitative ones, while creating a space for hybrid fields such as ludomusicology.

These two projects offer insight into one of the many ludological themes brought to the forefront at this year’s conference. Although too numerous to fully document, I also had the chance to take in presentations on a few other game-related digital humanities projects: speculative research on MMORPGs as digital museums, a cultural analysis of chat moderation on Twitch, and a interrogation of emulators as library resources. These presentations brought a diverse range of scholars together to discuss how game studies can be framed within the digital humanities. It was exciting to witness how the field fosters a collaborative academic space – one that I was happy to be a part of!