[WARNING: There are a lot of feelings in this post and there is a lot of frankness — about mental health, mostly. MUCH FRANKNESS AHEAD. If that’s not for you, you probably shouldn’t read this.]

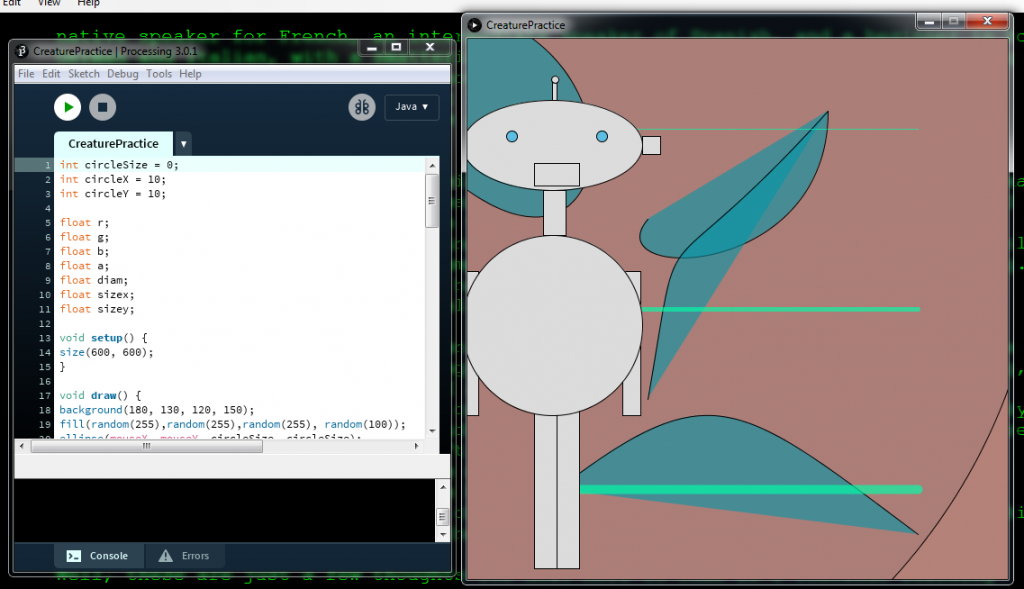

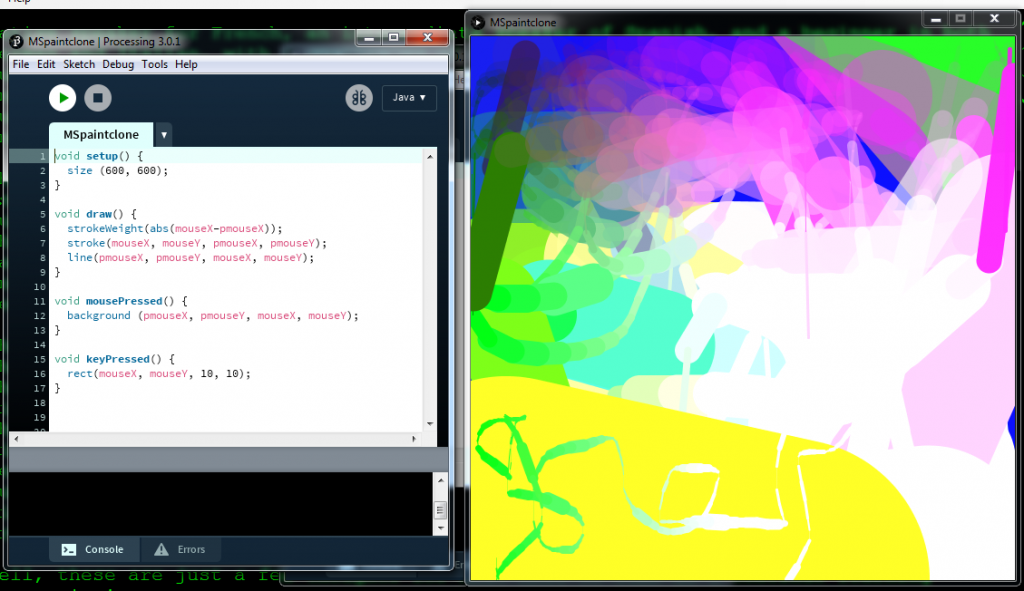

This past semester, I learned how to learn to program (no, that’s not a mistake). With the help and guidance of Rilla Khaled and Pippin Barr, I first learned Processing (Daniel Shiffman is a great programming teacher) and then after a brief evaluation of p5.js, moved on to Phaser and JavaScript.

[A note on guidance: all this learning actually happened under the guidance of a whole community of programmers both in and outside of TAG lab. When I couldn’t figure out how to space out the flower petals around my stem in a Processing exercise, the community was there to help. The other day, when it turned out that I hadn’t learned enough about object-oriented programming in JavaScript to properly manage states in phaser, the community was there to help. So, thank you, community.]

For something that I had been dreading for so long, it was revelatory to find out that I enjoy coding — like, really enjoy it! When the pressure is off and I can appreciate the puzzle of figuring out what to do, I like writing code a lot. This should come as no surprise: I love learning languages, which is why I know, in addition to English and French (the ones that I had to learn), Spanish, a bit of Italian, a bit of German, and an anime fan’s Japanese (so, also not very much).

But, the final project for this class is one of the hardest games that I have ever had to make. It was difficult for a variety of reasons. In my last post, I mentioned how Tom was getting ready to leave for RCMP training, and how I could think of little else, creatively and otherwise. That’s why I decided to make a game about the month between Tom learning of the RCMP’s decision and leaving for Depot. I wanted to take away some of the event’s power by making a game about it.

As I also mentioned in my last post, I would normally never, ever, ever consider making a game (or any kind of writing or other creative work) about something that happened in my life so close to when it happened. Normally, I’d let such an idea sit in a drawer for a few years and then give it a go. But, as I mentioned before, this was hugely preoccupying for me. After being with Tom for nearly ten years and never being apart longer than that one time last year when I went to Europe for 45 days, I knew that this was going to be a big change, and probably a very difficult one.

And it was. I just wasn’t prepared for how hard. A lot of the reasons that made it hard for me to be without him, even though he was an email or a video chat away were because of things that we would normally deal with together — but more on that later.

At first, I didn’t have much time to devote to the game: I had to finish up my semester’s course work, fulfill my TA responsibilities, get Tom ready to leave for the RCMP, and be present for a friend that was also having a hard time. I chose to prioritize my relationships with people that I cared about, and would do so again. And that’s where the time went, up until Tom left.

After Tom left, the game was my priority. I had finished my course work and everything else could be put off for a while. I went into hermit mode and started working on the game. And that’s when my 96-year-old grandfather went into the hospital.

Now, as someone who lives in a town with decent public transit, I haven’t yet acquired my license. We visit my grandfather fairly frequently, and Tom usually would rent a Communauto (car-sharing service) car and off we’d go. I was upset that my grandfather was sick and that I had to rely on there maybe being space in my relative’s cars in order to go visit him, or possibly not visit him at all (as it turns out, I now have a standing offer from a friend to drive me so long as she’s not at work). I was upset because, at 96, even small ailments can be hugely important, and these ones weren’t so small. I found myself completely unable to focus on the project. I felt like my brain was betraying me – this was when I needed to be able to focus the most, and I was getting nothing done.

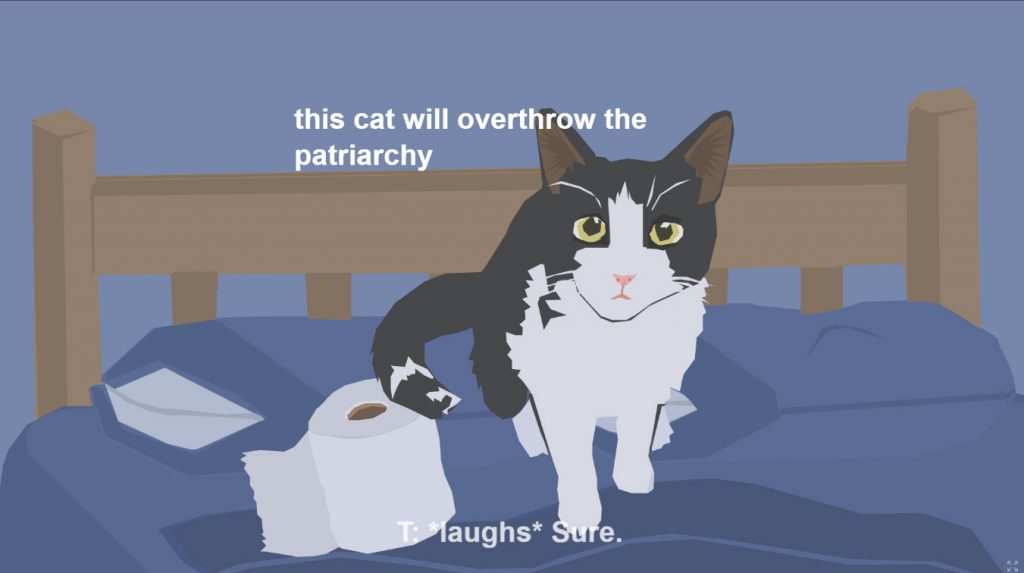

So, I left the scary parts for later. When I was able to focus, I did the parts that were familiar and pleasurable to me — I wrote dialogue, I drew pictures of my cat and my apartment, and I thought about the design of the game. But, when all that work was finished, the deadline was coming and I still hadn’t programmed anything. What’s worse, I couldn’t remember any of what I had learned all semester. On top of that, feeling like I might not be able to finish the project before the deadline was stressing me out even more, increasing the pressure.

I had actually chosen a slightly early deadline for the project, thinking that I would get nothing done during IndieCade East, which was happening right after the deadline and which was where we were going to show In Tune perhaps for the last time.

So, I fought back the feeling that I was somehow disappointing the people who had been so kind as to take time out of their schedule to teach me in a directed study this semester, and I wrote asking for an extension.

The relief was palpable when the extension was granted. That, along with the fact that, at that point, my grandfather was getting better and would be released any day, helped me regain my focus (unfortunately, he’s now back in hospital). Things went slowly at first, but working diligently through IndieCade East at the NYU MAGNET, with the support of some lovely friends there, I managed to program portions of my game. And I was enjoying it. And, given that this was my first time with JavaScript and Phaser, I felt like I was doing a pretty good job. I managed it! It had seemed impossibly stressful the week before, but things fell into place.

Well, so that’s how it was to work on this game. In terms of the workflow, what I would have of course liked to do differently is give myself more time to work on the project long before the due date – that’s kind of my style. But, up until now, I have had the privilege of an excellent support system that has allowed me to focus on my work, even when other things in my life were going on, and this was my first time doing without it. I’m not sure what I could have done differently about that.

That means that it’s time to talk about the game itself and the design decisions.

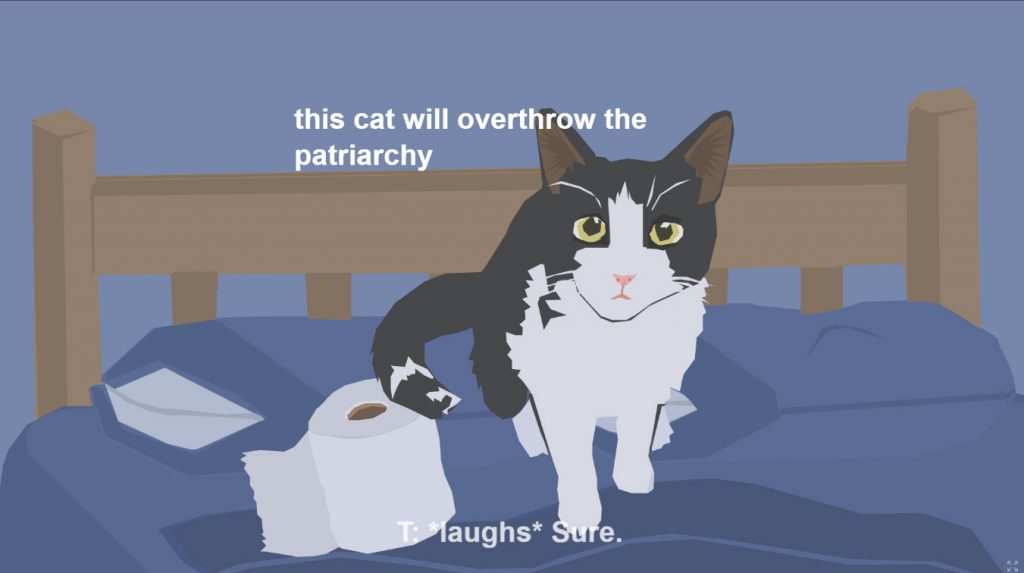

What I wanted to do in the game was juxtapose some version of the conversations that Tom and I were having about his departure with our cat’s daily shenanigans. As it says in the game, cats don’t care about human drama. They don’t understand it. So, what felt very dramatic and important to me didn’t have much of an impact on our cat at all.

I like the juxtaposition. The game is pretty slow-paced, so there’s time to read the conversations and interact with the environment (at least, I think so). My worry is that there aren’t enough animations to keep the player engaged in each scene.

For this project, I had to scope very tighly given the time frame, but I was also sick of certain of the choices that I usually make while making games on a short timeline. Namely, I wanted to try a different art style. I was sick of making pixel art for these short little games. This was at odds with the fact that I didn’t have much time to work on the game. Each individual animation was taking way too long to make. So, I had to make the decision to do story-board style animations, with very few keyframes and a simple style. Overall, it’s not what I had originally envisioned but I’m happy with the result given the timeframe.

I’m not a professional animator – I just dabble. What that means is that even the storyboard-style animations took enough time that I made relatively few of them. I wish that I could have made more of them, because I wanted to them to function as a visual reward for the player. How I made up for it is made it so that when you click the cat, messages about the cat appear, and I find those fairly entertaining. But that might just be me.

Of course, the most important thing to me about this game is that I programmed it myself in Phaser/JavaScript and that it works. That’s a big milestone for me. It was also one of the main goals of this directed study, so I’m happy that I managed it. It’s an empowering feeling, even if I know that I might struggle just as much the next time that I sit down to program something. I’m okay with that — knowing that I can do it at all is huge.

[This game is available for play here.]