[I’m pleased to share that an article based on the research originally presented at CGSA 2017 has been published in a special issue of Game Studies about queer game studies. You can find the special issue here. You can find my article, entitled “Queering Control(lers) Through Reflective Game Design Practices” here. The research has developed quite a lot since this initial talk on the subject, so I highly recommend the Game Studies article rather than this post.

Should you need access to the slides and talk as they appeared on this blog, please find the original post below:]

[This year, at CGSA 2017 in Toronto, I showcased The Truly Terrific Traveling Troubleshooter, gave a talk called “Queering Game Controls” and chaired a panel. I thought I’d share my slides along with the rough-not-quite-what-I-presented version of my talk, along with a few notes about the kind of discussion that took place afterwards. I’ve kept the slide-change cues in the talk in case anyone wants to follow along. My travel to CGSA this year was funded by the Concordia Faculty of Fine Arts.]

Slides on Google Docs: https://goo.gl/f1Ei7M]

QUEERING GAME CONTROLS

“It is not simply that queer has yet to solidify and take on a more consistent profile, but rather that its definitional indeterminacy, its elasticity, is one of its constituent characteristics.” (Annamarie Jagose, Queer Theory: An Introduction)

When I was conceptualizing this talk, I was thinking about the topic of queerness and game controls through the lens of visibility, through hypervisibility, through invisibility. I am a queer nonbinary person married to a cis man who came out in 2016, after first realizing that there was language that existed that described my experience, and then deciding that I wanted to use that language for myself. Being assigned female at birth, my marriage and relationship to a cis man has at times erased other aspects of my identity, since people make a lot of assumptions from that. So, all this to say that my experiences with queerness are reflected in my work as a designer, and the concept of visibility is something that I think a lot about. I come to this talk as a queer game designer and doctoral student. [slide]

Words like queer and genderqueer allow me to express my experience as part of a multidimensional spectrum rather than a binary, and the flexibility of their definitions is something that I value. That “definitional indeterminacy” extends to the concept of queering game controls (ibid.). For the purpose of this talk, game controls refers to both the physical and digital aspects of control that allow players to interact with a game. I’ll be talking about control literacy, game feel, flow, procedural rhetoric embedded into controls, player agency, materiality and embodiment, subsequently queering each concept using examples from my own work and the work of others. Afterwards, we’ll open up into a roundtable discussion. I’ll try to leave about half our time for discussion. [slide]

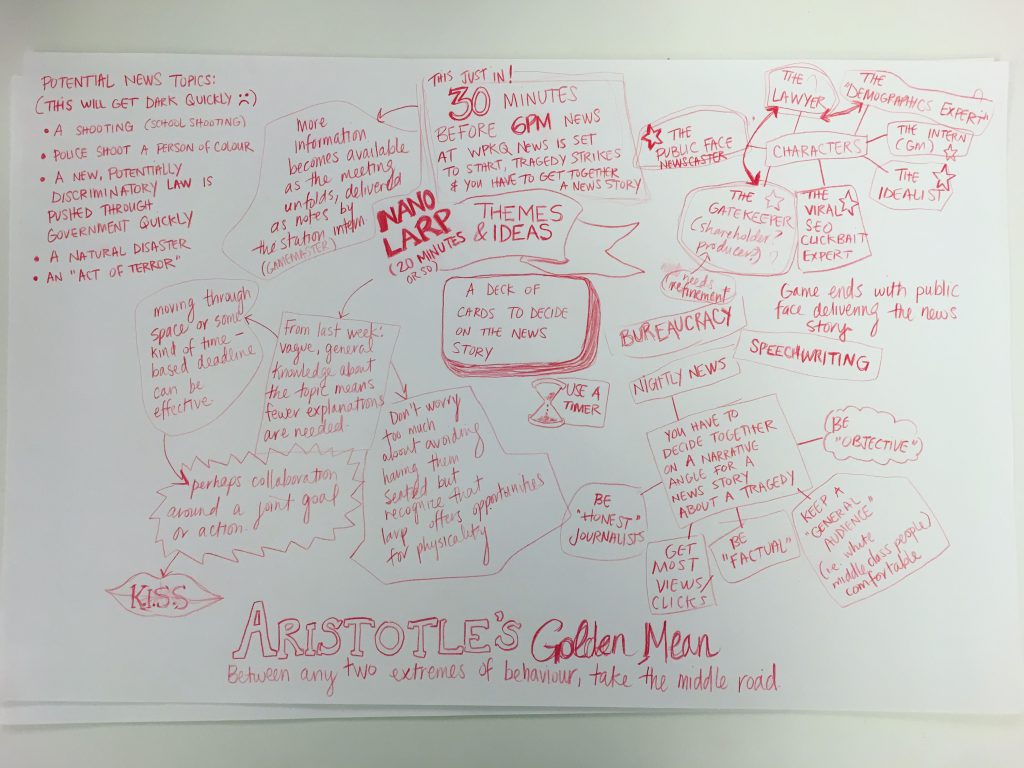

DESIGN EXERCISE

Actually, as part of our discussion, I’d like for you to do something as you listen to my talk. Don’t worry — hopefully it won’t be too distracting: I’d like for you to think of a game, a mechanic or a control that you think would benefit from queering, and think of some ways that it could be queered. At the end, I’ll ask for some folk to volunteer to talk about what they came up with. [slide]

CONTROL LITERACY

Control literacy refers to the ability to pick up and play with a given controller, whether it’s a mouse, a joystick, the standard gamepad, a touchscreen or a touchpad, the frequently standardized keyboard key-controls , or any other set of learned conventions that are often assumed when it comes to game controls. Many of you will, for example, know exactly what I mean if I say something like, “the controls are just WASD (‘WHAZ-DEE’)”. This literacy quickly becomes invisible for those who have it, and is a part of what we mean when we say that someone is “good” at games or technology. For a detailed analysis of some standard game inputs, see Chapter 6 of Steve Swink’s Game Feel.

Of course, literacy is a learned skill. Talking about the Xbox 360 controller, Anna Anthropy points out to us: “The amount of both manual dexterity and game-playing experience required […] makes play inaccessible to those who aren’t already grounded in the technique of playing games.” (Anna Anthropy 2012). Designers and those who are inculcated with this literacy make a lot of assumptions about these standard control schemes. When we think are dealing with the default, we forget to ask ourselves about it at all. As Shinkle points out: “Rather than reducing the need for skillful engagement and the potential for error, such control systems demand their own highly-specific skillset.” [slide]

GAME FEEL

This brings me to the next term that we might want to be familiar with to facilitate this discussion: Game Feel. Swink defines Game Feel thus:

“Game feel is the tactile, kinesthetic sense of manipulating a virtual object. It’s the sensation of control in a game.” Game feel is easy to bring to mind, but difficult to understand and define. Game feel is about “moment-to-moment interaction.” Swink takes the normative best-practice stance that game feel that feels “intuitive” and that encourages the “flow state” is to be sought after. [slide]

FLOW

Flow, a term popularized by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s, refers to a mental state supposedly achieved when performing a task wherein the level of challenge is commensurate with the player’s skill. Gameplay must walk the line between boredom and frustration to fall within the flow channel. This is the Goldilocks approach to game design: not too hot, and not too cold. When players are in the flow state, we are told that they forget what’s around them and are totally involved, totally absorbed. Control literacy and “good” game feel, or at least, not distractingly bad, are prerequisites for reaching the flow state. [slide]

PROCEDURAL RHETORIC IN GAME CONTROLS

Next, I want to talk about what game controls tell us through their procedural rhetoric. At a very basic level, most games give their players a great deal of power through their controls. The average game tells us we can run without getting tired (unless we have a stamina bar), that we can leap high into the air, executing perfect, identical jumps each time, and that we’ll have no trouble activating complex machines at the push of a button or two. Finally, most games tell us, through the control that they give us that we will only get stronger over time. To quote Mattie Brice, “gamers are set up to be colonial forces. It’s about individuality, conquering, and solving. Feeling empowered and free at the expense of the world.” Players are used to having maximum agency and power within the rules of most games. [slide]

MATERIALITY AND EMBODIMENT

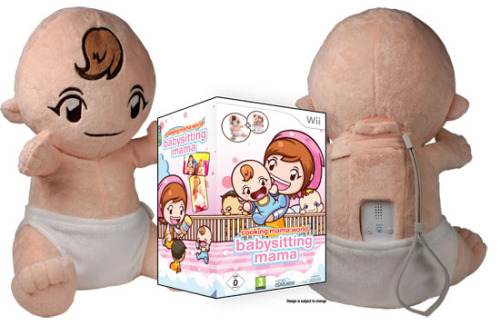

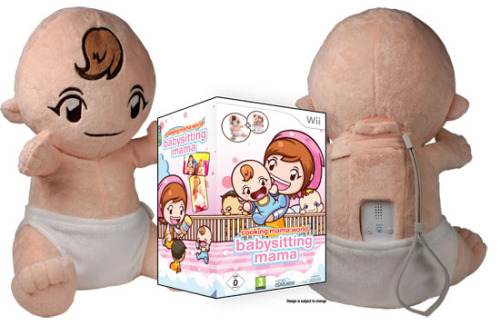

I want to introduce the concept of materiality as it relates to the status quo of games and game development. Standard, mass-produced game controls are objects of plastic, rubber and metal, with electronic guts inside. On rare occasions, the industry might produce something like this: [slide]

But that raises a whole other discussion about heteronormative design, and I don’t think that we can yet call this particularly subversive, unless, for example, we were to repurpose it to play a different game.

[slide]

The most common game controls have yet to move beyond plastic. That isn’t to say that there aren’t material differences among plastics. As Swink points out in Game Feel:

“The materials used to construct the device has an impact on the way the user feels about the controller, and therefore, the game. The white plastic that houses my Xbox 360 controller has a smooth, pleasingly porous feel. It’s almost like skin. My Wiimote and Playstation controllers feel like plastic. It’s a subtle difference and measuring its impact on game feel is extremely difficult.”

I’ve yet to see a commonly-accepted mass-produced game controller that isn’t largely plastic. It occurs to me that designers of another kind of toy have learned to make incredible things with silicone — maybe the game industry can follow suit. The controllers could even be waterproof. [slide]

QUEERING GAME CONTROLS

OK, so how are game creators, queer and otherwise, queering game controls? What are some examples of subversion related to these standards and best practices?

Amongst alternative game creators and artists, hacking or repurposing of industry-produced controllers is common, especially with the Kinect and PlayStation Moves. Other creators are changing the relationship of the player to the controller and controls, forcing a new paradigm. Yet other projects create custom controllers, tying the game mechanics and the game intimately to the means of controlling it. As Annamarie Jagose tells us, queer is definitionally flexible, and so is, I think, the act of queering. That’s why I think it’s most useful to point to specific examples at this point from my own practice and from some others, rather than trying to form a general theory of how to queer game controls. [slide]

Before proceeding, I want to take the time to problematize “flow” as a desired state. Brian Schrank points out in Avant-garde Videogames that “Games or cultures that foster flow allow people to be perfectly subjugated within their systems. When a system is designed with optimal flow, people forget that they are being subjugated: their doubts and distractions are kept to a minimum, and all human labor is positively absorbed into the system.”

In their 2016 GDC talk, Designing Discomfort, Dietrich Squinkifer suggests that there is “untapped potential in using gameplay itself to take the player out of flow and instead deliberately invoke uncomfortable emotions,” and that furthermore, this is necessary for the maturation of games. [slide]

Before it was even a conscious part of my game design practice, I have been making games that take what is invisible and make it visible again, often making the invisible hypervisible. Leveraging awkwardness, discomfort, imbalance and other queerable concepts is one of my core design approaches, creating indeterminacy and unsettledness. In my games, I create spaces for critical reflection and conversations, a practice perhaps best explained by Rilla Khaled in Reflective Game Design, which she outlines as privileging questions over answers, clarity over stealth, disruption over comfort, and reflection over immersion. [slide]

In The Queer Art of Failure, Halberstam suggests, “Under certain circumstances failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative, more surprising ways of being in the world.” Queering design provides non-standard ways of creating as an alternative to the hegemonic best practices that govern the game industry. Queering can serve as both design philosophy and desired outcome for player experience.

With all of this in mind, I propose that we can and should create gameplay experiences by taking players out of the flow state: let the game be slow, let players be bored, or frustrated, or any number of the other emotions that are part of the spectrum of human experience beyond the limited set that flow and industry best practices encourage. Let them remember that they have bodies, and encourage them to think about that embodiment. Let them interact with

something other than plastic. [slide]

I’m going to talk about some games that I think demonstrate some strategies for queering games — not all the games are by queer designers, but they all subvert expectations around controls in ways that are useful touchstones for our discussion. Given time constraints, I’ve prioritized examples from my own practice and games by teams with queer creators.

The games that I propose fall under four “ways of queering” controls, although they may fit under multiple categories at once, which are:

Queering Common Control Schemes

(Un)common Technologies

Living Entities Touching Each Other

Controls as Theatre

As you might be able to tell, these categories are far from exhaustive — I have included them to suggest some of the ways that I think might be generative for pursuing future queering of game controls. [slide]

QUEERING COMMON CONTROL SCHEMES

A common problem that I encounter in my work is, oddly enough, for a queer games talk, reproduction. I often work with custom controllers — a category that we will talk about — but that means that it is difficult for me to digitally share my work. Games in this category subvert commonly-found game controls in satisfying ways. [slide]

A Series of Gunshots (2015)

by Pippin Barr and Rilla Khaled

A Series of Gunshots is a game by Pippin Barr in collaboration with Rilla Khaled that wrestles with player agency. In a blog post about the game, Barr had this to say about the controls:

Why just any key? And what about the mouse? I had a build that included a mouse click to trigger the shots as well, but it quickly became obvious that that has too much implied directed agency (you click somewhere specific) which messes with the ‘involved and not involved’ feeling I want the game to have. The fact it’s any keypress (again, not, like the spacebar only to avoid the sense of having a specific agency, a trigger) makes your involvement both critical (it’s the only thing that makes the gun go off) and abstracted/distant.

Why can’t you see the shooting? Well, you can – you see a flash in a window (or conceivably in an alley or a car, say), but you can’t see the people or the gun or ragdoll physics or any other details. That’s for two main reasons. The big one is I’m aiming for player interpretation and imagination within this highly constrained and minimalist interaction, so the less seen the better. The other one is that to the extent this game is ‘about’ shooting in games (and in life) I want to avoid any sense of ‘rewarding’ the action with visuals, physics, etc.

In Barr and Khaled’s game, you can chose to shoot or not shoot, but you don’t know who is shooting who, or why. Shooting is divorced from the usual narrative justifications for it, although of course the buildings and architecture do suggest a setting. [slide]

Seventy-Eight (2014)

by Allison Cole, Jess Marcotte and Myriam Obin

In 2014, I made a short platformer game called “Seventy-Eight” with Allison Cole and Myriam Obin. The title is a reference to the difference (at the time, and not accounting for intersectional identities) in pay between men and women — for every dollar a man made, a woman could expect to make seventy-eight cents. In this game, you play a woman who can’t seem to please the system. Made in a weekend at the GAMERella game jam, the game features audio recordings of gendered insults that we asked other jammers to record, based on what they might expect to hear aimed at a woman who was considered to be underperforming, a woman who was considered to be performing at a normal level, and a woman who was thought to be overperforming. The appropriate audio plays when the character is at the bottom of the screen (underperforming), the center (performing adequately), and at the top of the screen (overperforming). The character is damaged if they are either too much to the bottom of the screen or too high up.

In programming this game, I created phantom key presses and invisible changes to the platforms that would cause the avatar to jump or walk without player input, as well as making platforms lose their collision detection boxes at random, causing the avatar to fall through. These were deliberate choices that were meant to make the game feel systemically unfair, but they read so subtly that they felt like glitches or mistakes. These were meant to procedurally represent the invisible forces of systemic oppression that might trip people up in the workplace.

The intent was to create a feeling of paranoia in the players causing them to wonder whether or not the system was against them or if their own performance was inadequate. Such feelings of not knowing are common to the experience of marginalized people. But ultimately, despite the careful theming, there was no way for players to know about these programmatically enforced rules related to the controls without being told. The result was that players expressed frustration because they didn’t know that this was happening.

Ultimately, I don’t think this experiment was successful, but I still think it is instructive for thinking about how we might use the queering of game controls to develop games in the future. [slide]

(UN)COMMON TECHNOLOGIES

Now I’d like to talk about games that use (un)common technologies, by which I mean technologies that are mass-produced and readily available for purchase, as opposed to custom controllers, but that might not be in every home with a console or computer. [slide]

Hurt Me Plenty (2014)

by Robert Yang

In Robert Yang’s “Hurt Me Plenty,” the player takes on the role of a Dominant negotiating boundaries with a partner who they are about to spank. The player negotiates how hard they will spank their partner, what clothes the submissive will wear for the spanking, and a safeword. The game randomizes the title that the player’s partner uses for them.

If the player violates their partner’s boundaries in the game, the game can lock the player out for hours at a time, potentially days, depending how seriously boundaries have been violated. This means that if the game is being showcased at a festival, and one player violates these boundaries, all the festival-goers can be locked out for hours. As Yang notes “Your trust, safety and politics affects the entire community” (Indie Tech Talk #23 Cheeky Design, NYU Game Innovation Lab 2014). This denial is powerful because players are used to being catered to and to being in control.

Although players can buy the game to play at home, the festival version of “Hurt Me Plenty” makes use of the Leap Motion controller, a control that can register the speed and movement of a person’s hand in the air. The problem is that this controller doesn’t actually always work that well, and can be finicky, which means that potentially, players may not have quite the right technique with the leap motion, and might accidentally flick their wrists too hard, or become frustrated with the control and overdo their next motions. The possibility of mistakes in this scenario seems like it might be quite generative. [slide]

LIVING ENTITIES TOUCHING EACH OTHER

I want to recall Swink’s earlier words about the porous plastic material of his Xbox 360 Controller. He said, “It’s almost like skin.” Well, these games are about touching the skin of a living other, whether human or otherwise. [slide]

In Tune (2014)

by Allison Cole, Jess Marcotte and Zachary Miller

“In Tune is a game that deals with bodies, their interactions, and giving/withholding consent. Players are asked to negotiate and communicate their own physical boundaries with a partner using skin-to-skin contact as the main controller of the game.”

(Cole, Marcotte and Miller 2014)

The controllers for this game are comprised of PlayStation Move controllers, a Makey-Makey, and a pair of hand-sewn conductive sleeves.

In Tune uses consensual touch as one of the main mechanics of the game. With a partner, players are asked to examine a physical pose modeled on a screen by two artist’s mannequins. Players then discuss whether they wish to complete the pose, and if they do, how they will do so. The game is focused on negotiation of boundaries, and as such, it is possible to decide to modify a pose to make it more comfortable for those playing. This is one reason why during the development we thought about and discarded the idea of using something like the Kinect. The accuracy of the poses isn’t as important to us as the negotiation.

Should players decide not to complete a particular pose, they simply skip it, and are presented with a new one. If they decide to complete the pose, they hold it for 13.5 seconds, enabling them to consider the experience without turning the game into a problematic version of “chicken.” If players interact while one player is not consenting (a state that they signal through a button on the PlayStation Move), the game provides audio feedback in the form of radio static, vibrating controllers, and bright red lights at the tip of the Move. After a pose is completed, players are presented with a prompt that is intended to help them to reflect on the experience or deepen their relationship with their partner. Such a prompt might, for example, ask players to recommend media to one another, do their best chicken impersonation, or name something that the other player has done well during the last interaction. The poses are not ranked in any way, and the same pose can appear twice. This allows for people’s different personal histories with intimacy, and also allows for people to reconsider the same pose. They might have said yes to a pose, and decide the next time that this wasn’t a comfortable experience for them, and so say no this time. On the other hand, they may not have felt comfortable with a pose when it was first presented and skipped it, but after getting to know the game and their partner, they may wish to say yes the next time they see it. Some poses are also deliberately challenging for a number of logistical reasons, encouraging players to say no for reasons other than just the relative intimacy of the pose. Power dynamics are also included as a factor, with some poses mimicking power exchanges.

Returning to this idea of visibility, In Tune makes visible consenting bodies. In our day to day existence, or when we grow familiar with people, we may neglect to ask them whether it’s okay, to, say, give them a kiss or a hug. As one of the designers of the game, who has also played it a great deal, this game reminds me that there is pleasure in the asking. [slide]

We Are Fine, We’ll Be Fine (2015)

by Raoul Olou, Hope Erin Phillips and Nicole Pacampara

“We Are Fine, We’ll Be Fine” by Raoul Olou, Hope Erin Phillips, and Nicole Pacampara, was initially developed at Critical Hit 2015. This game, which features a beautiful wooden game board, is set up like a ritual or seance. It leverages social contract and social behavioural rules to be able to keep players playing once they’ve started, since the game requires three players. When players connect to each other in different configurations by touching each other’s hands while also touching designated spots on the game board, audio clips play. The audio is made up of interviews with marginalized people who tell stories about their experience with marginalization. The players only have the option to listen and to hold on to each other. The game resists the temptation of giving players more agency than activating the game board, holding each other’s hands, and listening. Players can’t try and fix the situations and they don’t add to the archive of sounds. [slide]

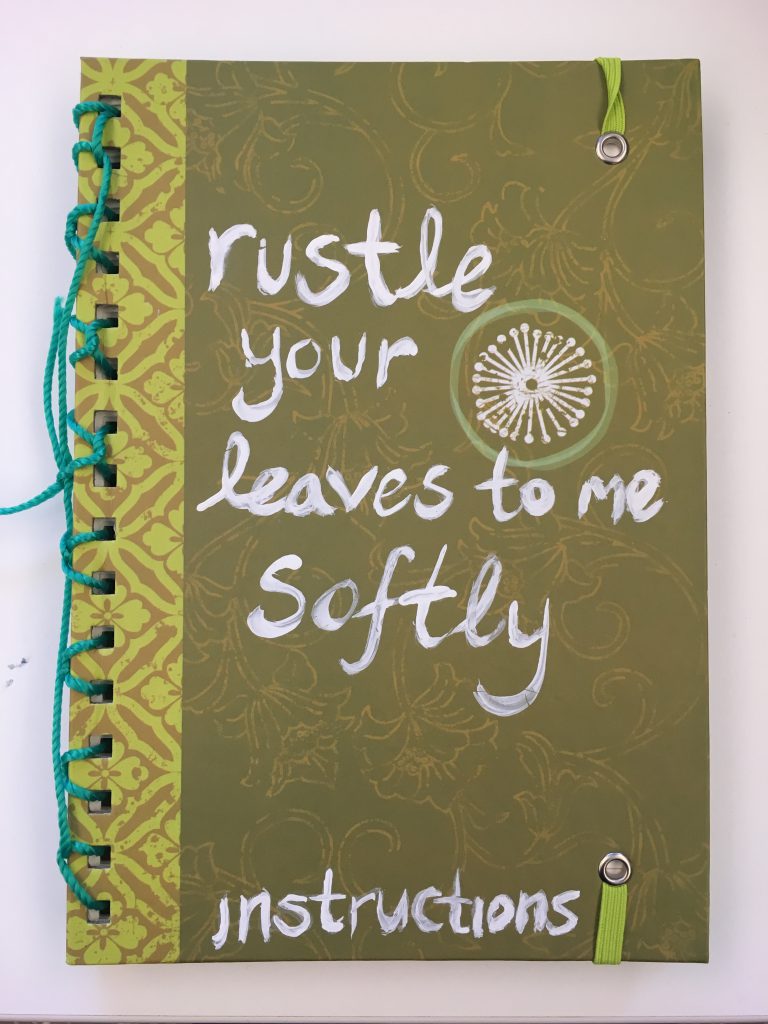

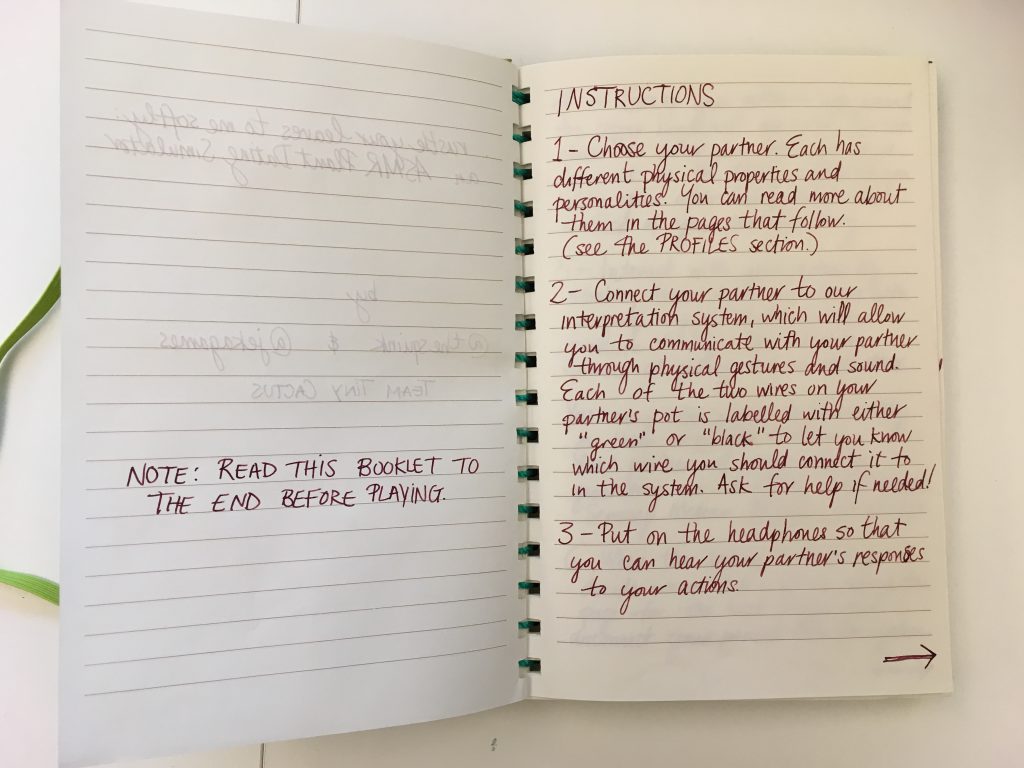

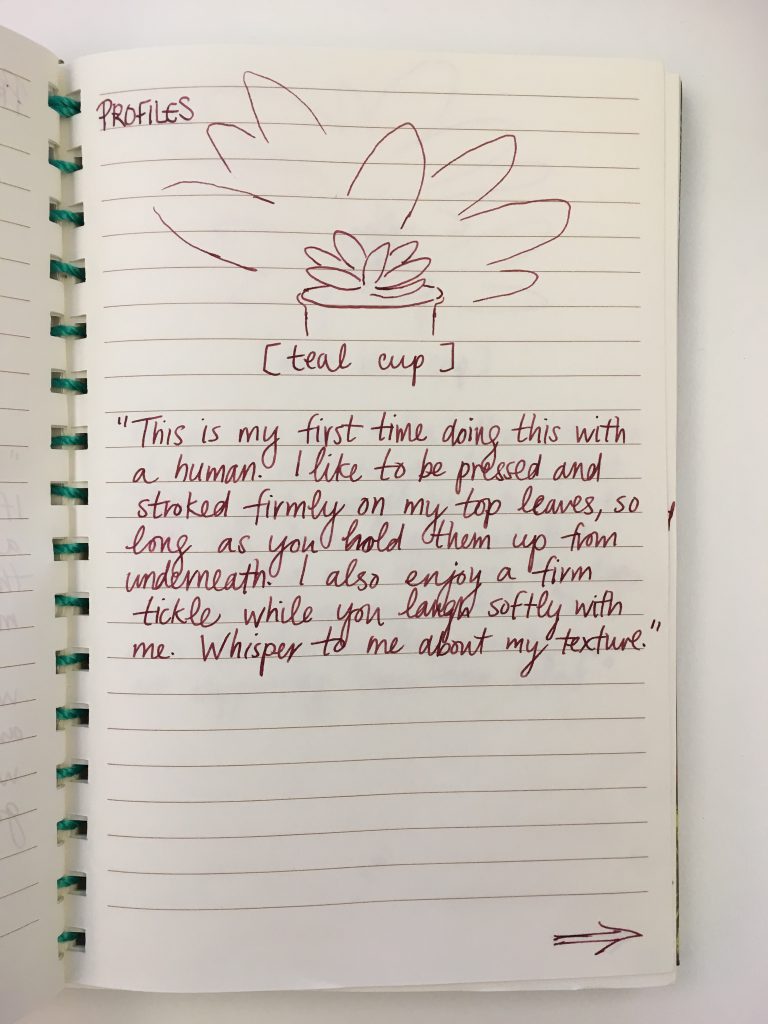

rustle your leaves to me softly (2017)

by Jess Marcotte and Dietrich Squinkifer

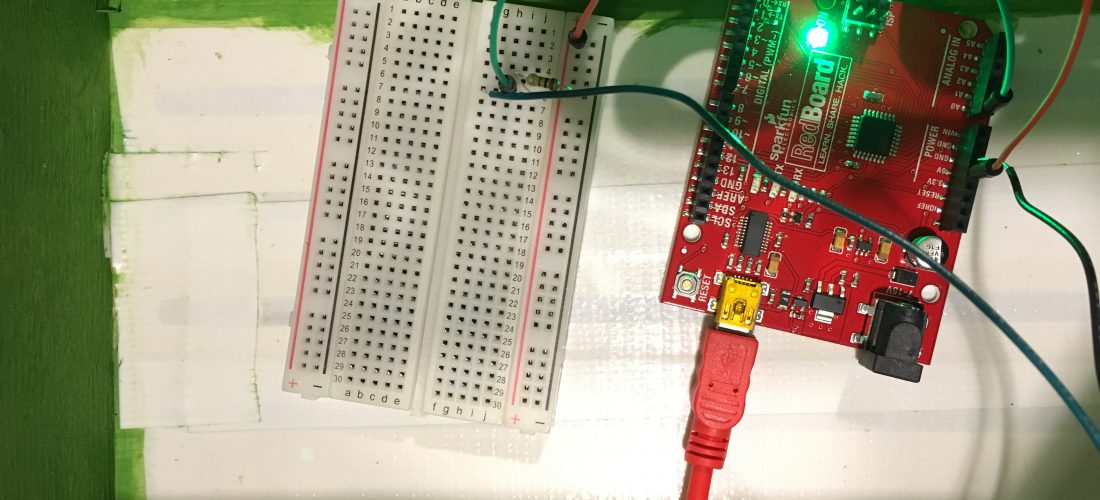

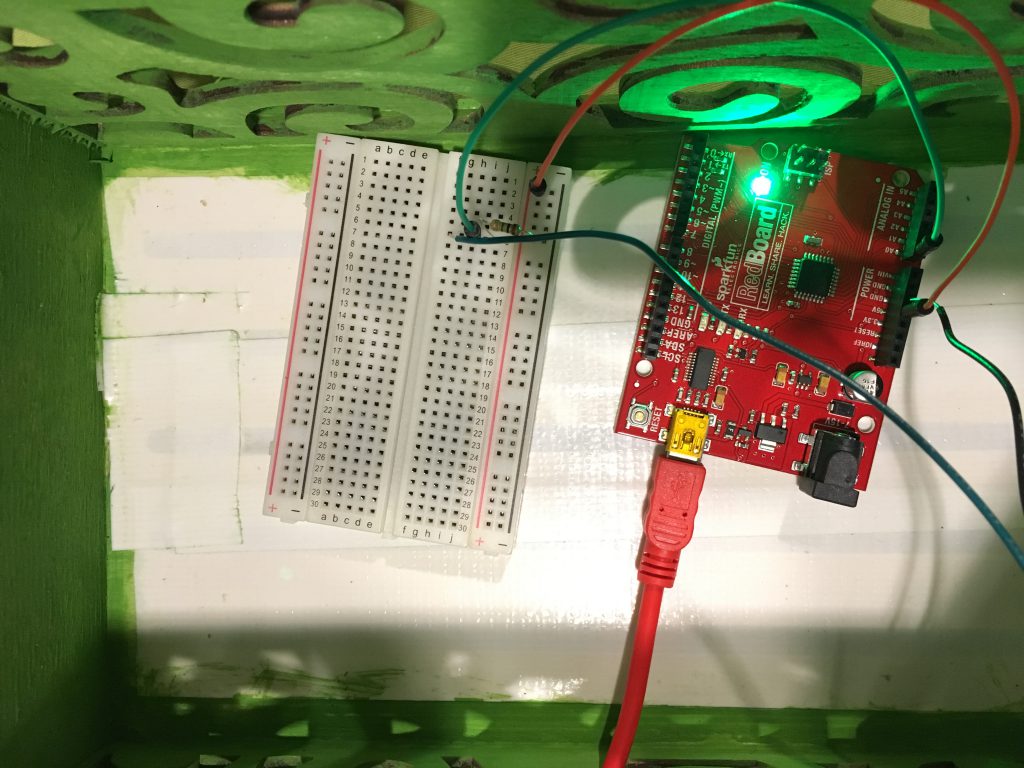

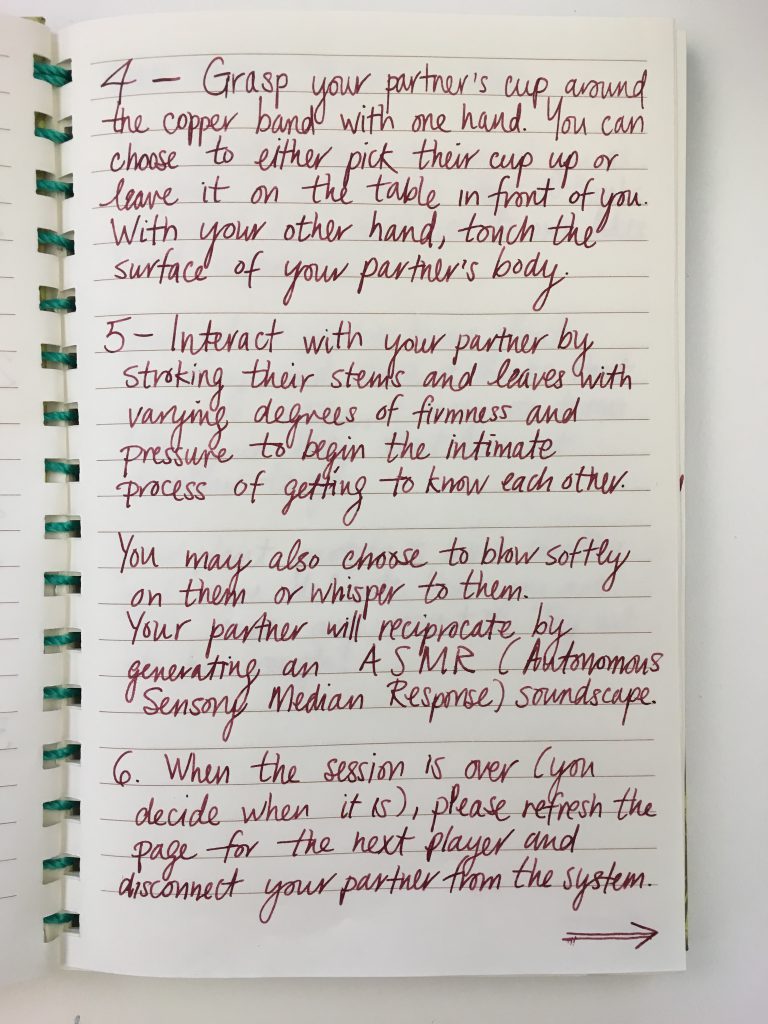

The full title of this game is “rustle your leaves to me softly: an ASMR plant dating simulator,” and in it, players form a relationship with one or more plants. This screenless game, made by myself and Dietrich Squinkifer, uses touch as the main interaction of the game, with sound as feedback. From my end, the game was inspired by discussions with Ida Toft around designing for an other that we can’t necessarily know the mind of. The controllers are made up of ceramic cups, copper tape, and wire, with one wire wrapped around a screw that is then stuck into the moist dirt that fills the cup. These are hooked up to an arduino board with a very powerful resistor. The entire setup is hooked up to a computer reading a web-based javascript program. This setup facilitates an interaction between a plant and a human. There are a number of factors in productive tension here.

As the human touches the cup and the plant’s surface, a soundscape begins to play, layering itself and fading in and out according to the conductance between the plant and the human. The relationship that is built by this experience is partially fictionalized: the instructions for the game have dating profiles for each plant, suggesting what kinds of touches and other interactions the plant partner might enjoy, and the instruction manual also contains a section explaining that the plant is playing an ASMR soundscape back to the human in the hopes that it is something that they will enjoy. The Plant ASMR that results was written and performed by Dietrich Squinkifer and myself, designers trying to think like plants trying to appeal to humans.

Fictionally, the plants also enjoy this relationship — we can’t access the consciousness of these plants to determine whether or not they enjoy being touched, although there are number of articles that have come out recently talking about plants and their sensory organs, such as a BBC Earth article that came out just before this game was made entitled, “Plants Can See, Hear, Smell and Respond.” Still other research by Dr. James Cahill (University of Alberta) talks about how some plants may benefit from or “enjoy” being touched, while others are harmed by it. So, we can’t know for sure about these particular plants. This is part of the fiction of the game.

On the other hand, the conductance, and therefore each plant’s personality, is based on the plant’s physical properties as well as the physical properties of the human player. Touching the plant in different places, with different degrees of pressure or different types of touches varies the soundscape, and humans themselves offer different skin conductance based on the dryness of their skin. These properties are not engineered, and the feeling of the human touching the plant’s skin is not made up. These physical properties form the unique character of the relationship between each plant and human, and I think the feeling of being connected to another living creature, even if it is mediated, is sincere.

The relationship formed, in the sense that is non-reproductive, is queer. There is also a sense of transgressive intimacy that comes from the fact that the game is generally played in front of a public audience, but that the plants come off as well…uh…quite thirsty. Plant metaphors – root, stem, bud, flower, etcetera are deeply embedded into romantic poetry traditions, meaning that words that are perhaps innocent when they refer to plants become sensual, even erotic, when contextualized in the game’s whispered ASMR soundscape. [slide]

CONTROLS AS THEATRE

It is possible to critique some custom controllers by saying that all that they do is reproduce extant control schemes without adding anything meaningful to the experience. Just because a button isn’t on a standard controller, that doesn’t mean it will create more meaningful interactions, or serve to make a better game. Under this category, I have included one of my latest collaborations with Dietrich Squinkifer, The Truly Terrific Traveling Troubleshooter, as an example of a physical-digital hybrid game that brings the fictional setting of its game world into the spaces that it visits. [slide]

The Truly Terrific Traveling Troubleshooter (2017)

by Jess Marcotte and Dietrich Squinkifer

You may have had the chance to play this game yesterday at lunch. The Truly Terrific Traveling Troubleshooter is a radically-soft game about emotional labour and otherness that fits entirely inside of a carry-on suitcase. One player takes on the role of the Troubleshooter and the other is a Customer with a trouble. Assisted by the Troubleshooter’s toolkit, the SUITCASE (Suitcase Unit Intended to Cure All Sorts of Emotions), the players work together to find a solution to this problem by following a series of steps. At the end of the encounter, the Customer decides whether or not the terms of their agreement with the Troubleshooter have been fulfilled, and whether the Troubleshooter has earned their payment — a coupon upon which a method of payment is represented.

There is a lot to say about emotional labour, radical softness and otherness, but I’ll focus on materiality and controls for the sake of this talk. First of all, all the “buttons” in this game are handcrafted objects which were crocheted or sewn by Dietrich Squinkifer and myself. I then embroidered the objects with conductive thread. There are nine objects: a fish, a beaker, a scroll, a lizard, an eyeball, an ear, a heart, teeth and a plant. When “consulted,” the objects play different statements which are then meant to be interpreted and serve as inspiration to working on a solution for the Customer’s trouble. The objects are meant to be interpreted in multiple ways by Troubleshooters and Customers alike, without a perfectly defined meaning. So, touching the teeth, for example, is as likely to yield “take a bite out of your enemies” as it is to say something like “talk it over.”

The soft, yielding tactility of the objects was similarly important to our design, suggesting a vulnerability and an openness that contrasts with the hard shell of the suitcase that houses them. Inasmuch as possible, everything that comes out of the suitcase (except for packaging materials that protect the objects inside) is diegetic to the universe of the game, including the Troubleshooter’s certificate from the Institute of Emotional Labour, which serves as a character sheet, the headphones, which are painted an antique gold, and the Troubleshooter’s manual, which is a hand-bound set of gameplay instructions. Embroidered upon the tablecloth are the game’s grounds, which are both functional and decorative.These are the ways in which the objects help to set a stage and assist players in getting into character. The physical objects in the game are also meant to serve as inspiration for improvisation, as well as to give the Troubleshooter something to fiddle with as they think. [slide]

A FEW CLOSING NOTES

*The status quo quickly becomes invisible or normalized.

*Game controls require a literacy that not everyone may have.

*We can create controls that destabilize standard control literacies.

*There are other interesting states and effects that game designers can aim for besides the flow state.

*Players are used to being powerful in mainstream games, but playing with that agency and that power can be generative.

*Making the invisible visible again, or even hypervisible, can be a generative design exercise.

*Alternative controllers can leverage materiality and embodiedness in ways that support queering, so long as they create interactions that are meaningful to the game. [slide]

[I’ve done my best to remember as many of the topics and themes of discussion that took place in the second half of the session, but wasn’t able to take notes. Apologies!]

DISCUSSION PERIOD

* One audience member talked about a friend who loved the idea of LARPing intimacy, but because of experiences in their background, was not down with the physicality involved. We briefly discussed ways of including intimate content/intimacy related content in LARPs without players having to act out these sequences, such as the fade-to-black technique, Ars Amandi, and countless others.

* One audience member brought up the innovative ways that Board Games are already leveraging controls and embodiment, such as by modifying the way that people make use of their bodies (specifically, the example of a game that uses a dental dam to alter the shape of a person’s mouth, distorting their speech). A fellow audience member noted that such uses of the body can be uncomfortable for some folks or even ableist, given that they often mimic disabilities (such as having a speech impediment), and we discussed how players, at the end of the day, can simply take off the controller or decide to stop playing when it ceased to be “fun.”

* This led to a discussion of some creators’ frustration with the notion of “empathy games,” which are sometimes assumed to be created for people who do not have that marginalization to “learn what it’s like” to be marginalized in that way, but a short experience like a game cannot stand in for years of life experience. And, furthermore, marginalized creators are unlikely to be creating their games for the sole sake of educating someone else.

* Another audience member brought up the importance of documentation for alternative game controllers such as video, since the controllers themselves are so often hard to access.

* In response to the design exercise I introduced at the beginning of the talk, an audience member brought up the idea of trying to make a game that, the better you did by standard metrics, the worse you would do in the game. This also brought the idea of doing well at doing objectionable things, like in Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please, or like in Brenda Romero’s Train.

WORKS CITED

Anthropy, A. (2012). Rise of the Video Game Zinesters. 1st ed. Seven Stories Press.

Barr, P. and Khaled, R. (2015a). A series of gunshots [game]., Pippin Barr, Montreal, Canada.

Barr, P. (2015). A series of shots in the dark. Pippin Barr, Available at http://www.pippinbarr.com/2015/10/26/a-

series-of- shots-in- the-dark/

Brice, M. (2016), Death of the Player. Mattie Brice, Available at http://www.mattiebrice.com/death-of-the-player/

Halberstam, J. (2011). The queer art of failure. 1st ed. Durham: Duke University Press.

Jagose, A. (1996). Queer theory. 1st ed. New York: New York University Press.

Khaled, R. (forthcoming). ‘Questions over Answers: Reflective Game Design’, in D. Cermak-Sassenrath, C. Walker & T. T. Chek (eds) Playful Subversions of Technoculture: New Directions in Creative, Interactive and Entertainment Technologies, Springer, Berlin, Germany.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

Olou, R., Pacampara, N. & Phillips, H. (2015). We Are Fine, We’ll Be Fine. Critical Hit Montreal, Montreal, Canada.

Schrank, B. and Bolter, J. (2014). Avant-garde videogames. 1st ed. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Shinkle, E. (2008). Video games, emotion and the six senses. Media, Culture & Society, 30(6), pp.907-915.

Swink, S. (2009). Game feel. 1st ed. Amsterdam: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers/Elsevier.

Yang, R. (2014). Hurt Me Plenty [game]., Robert Yang, NYC, USA.