Hi everyone! As I’m neck-deep in dissertation writing right now, I thought I’d work through some of the ideas from a chapter in a blog post. If you have any feedback, I’d love to hear it!

As the 20th Century drew to a close, storm clouds gathered on the horizon for the Lego Group: not only was digital culture threating to shift the focus of toy buyers and shrink Lego’s market, but the company also had to contend with the approaching expiration of its US patent in 2011. The plastic toy giant looked ahead and saw a future, very shortly approaching, where its only advantages on the toy aisle would be brand recognition and established territory—an established territory that was already shrinking as videogame cartridges crept down the aisle. So that left the brand, and there, the company saw the potential in licensed theme sets: partner with trendy pop culture properties and appeal to multiple markets simultaneously. And so, in 1999, the Lego Group partnered with LucasFilm Ltd. in anticipation of The Phantom Menace to release Lego: Star Wars.

Since then, the Lego Group has developed more than 60 licensed themes from two dozen other companies ranging from Columbia Pictures and Viacom to Warner Bros. and Lamborghini. Meanwhile, they’ve expanded into every other conceivable media form: amusement parks, merchandise, apparel, breakfast cereal, film…and video games. Now, they not only retain their dominance in the toy aisle over all other pretenders: they’re on our TV screens and bed linens and backpacks, too. This was a paradigm shift for the Lego Group, where the company’s top management began considering the LEGO brand, rather than its actual products, as its top asset.

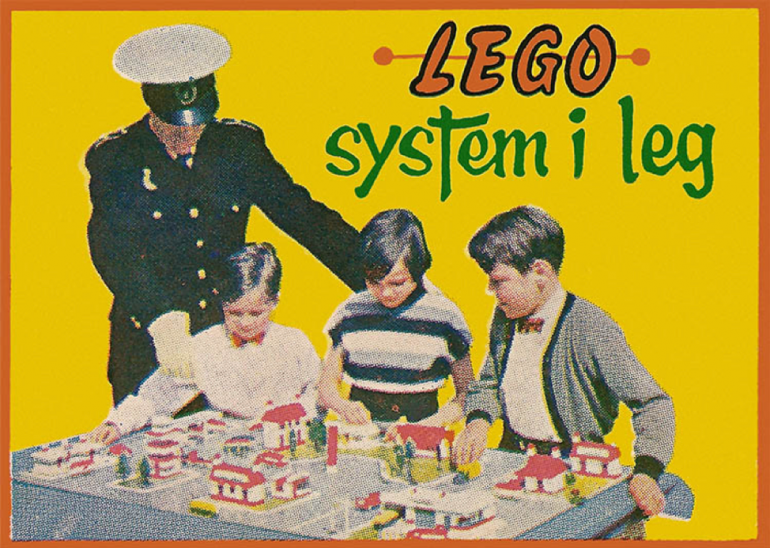

And slowly, over time, the brand came to overtake the product exactly as planned. But! The company had already spent some 50 years building its products around a core ethos called the System of Play. Introduced in the mid-1950s, the Lego System of Play formed a kind of ethos for the company’s products moving forward, and catalyzed the company’s primary focus on interlocking bricks. The system consisted of six desirable qualities for toys: unlimited play potential, suitable for girls and boys of any age, quality and attention to detail, and long hours of play that encourage development, imagination, and creativity. Interlocking bricks and construction sets, with their portability in terms of size and affordances for recombination, fit the bill on all counts. So moving forward, Lego took what it knew in terms of product design—the system of play—and adapted it to its own corporate culture as it struck out into the unknown territories of transmedia. And when we look at how that system of interlocking parts was applied to video games, particularly superhero video games, we stand to learn a lot about games and transmedia. But, if we want to do any of that, first we need to go back to the contracts that make all of this possible: licensing deals.

So how does licensing in Lego work? When Lego licensed its first properties to develop playsets, a clear one-way licensing structure was apparent: Lego goes to LucasFilm and partners with them to produce Lego Star Wars playsets. Lego, doing most of the work and producing and selling all the toys, keeps most of the profit and pays LucasFilm for the privilege of using their IP. This is how we traditionally think of licensing arrangements: a one-way contractor/subcontractor relationship, where one party owns the IP, the other party makes the product, and the two parties split the proceeds accordingly. But when Lego moved into other media, things got more complicated. Because now they’re licensing from someone else and then additionally sub-contracting with another producer to make the video game, movie, t-shirt or backpack. Because Lego makes Lego, not those other things.

But! Media consolidation has been extremely helpful to Lego here, because it turns out that those same rights holders they want to license from own movie studios. And video game developers. And sweatshops. So Lego can turn back around and just cut a deal where the companies they partner with for IP are one and the same with the companies they need to partner with to produce products. The question then becomes, who is the licensor and whom the licensee?

A great example of this is The LEGO Movie: Lego throws together all these different properties from Viacom and Disney and Fox and Warner Bros. Here again, games are very informative. Because you may note that the major game followup to the movie, Lego Dimensions, centers three characters: Batman, original character Wyldstyle, and Gandalf. The only thing these characters have in common are that all three are owned by Time-Warner. And guess what else Time-Warner owns? The studio producing the game!

That’s right, every Lego video game is made by a British developer called Traveller’s Tales (TT)—a studio that Warner Brothers Interactive Entertainment bought in 2007, just a few years after TT started producing Lego games. TT, under WB ownership, now exclusively produces Lego games, and it’s really found its fortune working with the Lego Group, creating action-adventure games with simple puzzle mechanics and basic control command structures then fused with popular intellectual properties lampooned by being represented in the slapstick LEGO minifigure form. In creating this style, TT and Lego were able to appeal to multiple audiences at once: various fandoms, parents, and young children. In making a successful movie tie-in film, TT was successful where other, better funded developers had failed, demonstrating that licensed games could be more than ancillary products. But such a point then raises the question of which license may have been responsible for the success.

And in working through those games, we begin to see very precisely how the System of Play—this modularity through interlocking components—maps to transmedia. So let’s look closely at some of those Lego superhero games. Lego has now developed three Lego Batman games and two Lego Marvel Superhero games, all of which have been massively successful. Batman and Marvel games are only unique amongst most other Lego videogames in that they have original stories (most follow the plotlines of the specific movies they parody). But the stories themselves don’t matter here, when the IP stable and multitude of signifiers to be drawn upon are so vast. Lego superhero games aren’t about experiencing a narrative but beating up blocks, solving puzzles through tool assembly, and playing in a world where everything is identifiable in self-parody.

The mechanics and code underlying these games are not specific in terms of the aesthetic response that they want to evoke. This is because virtually all of the aspects of, say, Lego Batman games designed with Batman specifically in mind are on the surface level, and all of those are worked upon by the signature Lego cutesyness. Meanwhile, the player uses the affordances of code to imagine both the locations and narratives of the licensed properties and the affordances of physical Lego pieces themselves.

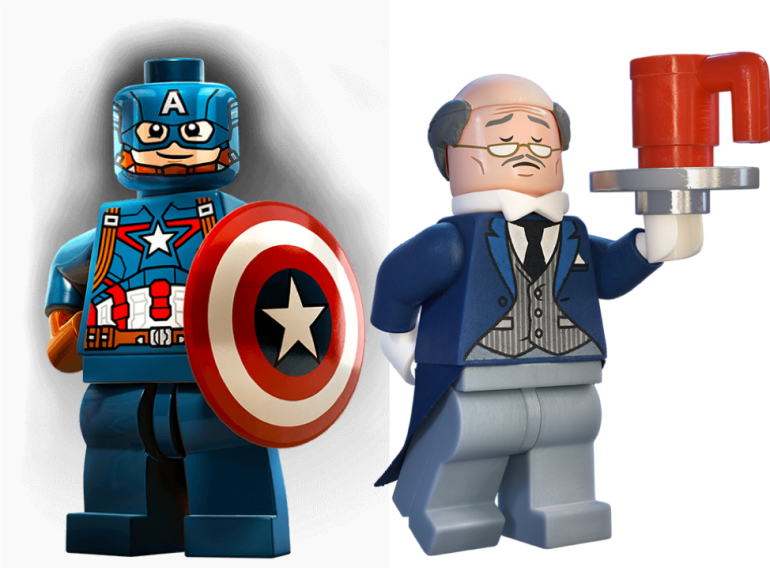

Due to the churn required in this system, many levels of skinning are called for. When licensing from a popular property, the Lego Group will skin that property over their core imaginary product. However, it stands to reason that the reverse is true, and the Lego Group is instead skinning itself over the property. This IP skinning thinly disguises the fact that all games in the series are rendered identically in terms of mechanics. Almost all TT Lego games have the same baseline mechanics in their gameplay, again recollecting the Lego System of Play: just as all Lego pieces are modular and can be swapped across different construction sets, so too is the TT code, swappable across various IPs. So if we look at LEGO Batman and LEGO Marvel Superheroes, the heroes of one transmedia universe are indistinguishable in function from those of another. The stretchy Plastic Man of LEGO Batman 3 uses his stretching powers to solve exactly the same kinds of puzzles as Mr. Fantastic in LEGO Marvel Superheroes. The same goes for Cyborg and Iron Man (both fly, interact with gold objects via lasers, and fire rockets), Solomon Grundy and the Thing (both are slow moving and can hurl large objects).

When we’re talking about superheroes, this just makes sense. These bros kind of are all the same. My favorite of all these though, and perhaps the most blatant and telling, is Captain America. In Lego Marvel Superheroes, Cap doesn’t throw his shield or bounce bullets off of it. Instead, his special ability is crossing over burning patches of fiery ground, using his shield to block the flames. You know who the analog for this is in Lego Batman games? It’s Alfred. He uses a silver tray to do the same thing.

A pattern begins to emerge.

In sum, an examination of the mechanics in TT Lego games reveals that such clear uniformity effectively flattens out some of the mysteriousness behind algorithmic systems. Users are left no closer to understanding the labour that goes into building software, but do come away with a better understanding of how code is disguised. This in itself is an exercise in media literacy, and players who comprehend the aggregation of labour and code infrastructure across products are able to move past thinking of the mechanics in Lego games as a “house style” and toward considering them as nodes in a network built around churn.

Wanna know more about transmedia? Get in touch with Kalervo or just give him a follow @kalervideo.